‘Will men keep explaining Dylan to me into eternity?’

To be a Bob Dylan fan has too often meant occupying ‘a world of men.’

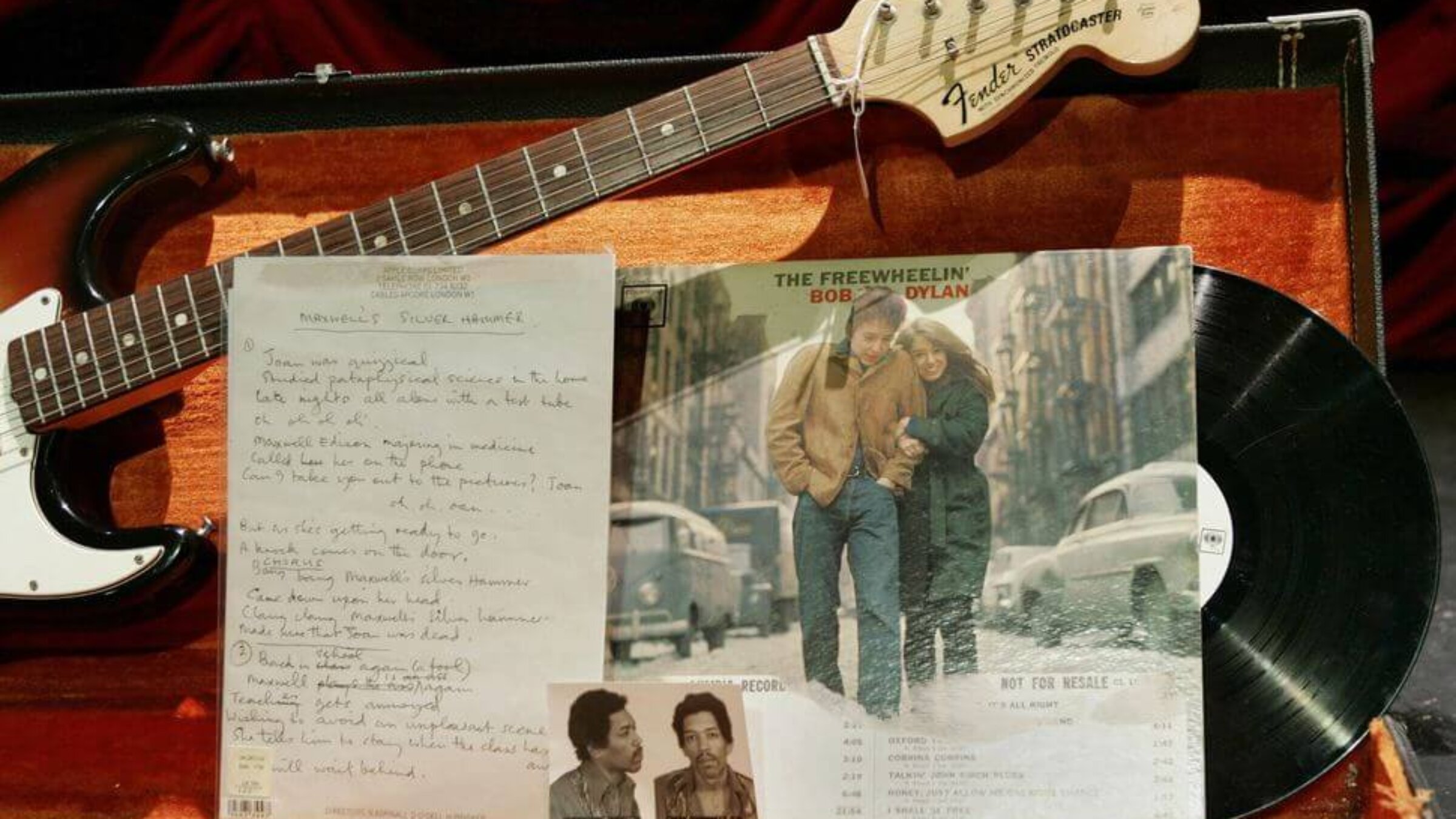

Photo by Getty Images

I was five when “Blood on the Tracks” was released (to mixed reviews) and the only Dylan I knew then, indeed the only Dylan I would hear before high school, was my father’s “Best of Dylan,” the singer-songwriter silhouetted against the blue cover, his wild Jewish hair shot with light, harmonica to his lips.

I didn’t come to the Dylan as I now view him until a guy I dated for five minutes my sophomore year of high school gave me an “Empire Burlesque” cassette. Take away the synth, and that album comes from the same place as “Blood on the Tracks,” both gorgeous medleys of ache, and it turns out that was what I sought. In everything. That 1985 album is in many ways the best and most consistent album to come since “Blood on the Tracks.” But other beauties preceded it, including “Desire” (with the backup vocals of Emmylou Harris and Ronee Blakely, powerful and excellent) and “Infidels” (Dylan’s return to the secular after converting from Judaism to Christianity, also excellent). It was a decade of exceptional work.

“Listen to the feeling, not the voice,” T said when I parroted the ridicule many in my generation felt for Dylan’s singing voice. Come to think of it, I was always being told how to feel about Dylan by men making an introduction, a tension I have felt consistently. My interest in Dylan has been big and bright and transformative, a highlight of my youth that was not all folly, and one that brought me to music and writing and resistance and various transgressions.

But that genuine interest also brought complicity with men: I would be the kind of girl who talked about Dylan lyrics, decoding them, like dreams, with the men who always seemed to know more than I did. It was a world of men, even though countless female singer songwriters were also making longstanding important work. I am reminded of my grandmother who once told me she went to law school so she could talk to her husband, a judge. I let men tell me about Bob Dylan over and over again.

It was J who gave me my first copy of “Blood on the Tracks,” Dylan’s 15th studio album. We were in college and we both had other lovers but there was something charged about this gift and my subsequent love of/ obsession with this album. I can see myself still in that room on Dartmouth Street in Waltham, Mass., playing the album, now a CD (along with Miles Davis’s “Someday My Prince Will Come”) on repeat. In all the genres of music I have loved — punk, ska, mod, jazz, rockabilly, rock, musical theater, new wave, pop, opera — I have always liked the sad songs.

“If You See Her Say Hello” was like a calling card for missed opportunity and at 20, I already thought I had missed all of mine. A laugh now, but that song holds the past present and future for me in one breath: I wanted you, I had wanted you, I will always want you. The listener is the subject and the object. Or the speaker and the spoken to. And while I skipped over the eight-minute one-liner that is “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts,” I listened to “You’re a Big Girl Now,” “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome,” and “Simple Twist of Fate” over and over again.

I have since seen Dylan perform countless times, in different stages of his life and mine. I have listened to many bootlegs, and The Bootlegs, and the Basement Tapes, and I have read his terrible novel, many biographies, and his “autobiography.”

One could call this scholarship and, in studying Dylan, I have learned to read the small bits of his life to which we are allowed admission. “Blood on Tracks” is powerful because of the filament between his access to his own suffering and our access to it. He was heartbroken over the estrangement from his first wife, and we got to see what blood on the page looked like for him. The blood of the country? We had seen it. The blood of criticism, and ridicule, the blood of all manner of transformation, we had seen it. The album came out of a period of respite after frantic touring, allowing him the space to sit with heartache. But that rawness is conflated by the control over and experimentation with the craft of music making in a variety of musical and storytelling traditions. We have the sense that Dylan, a recluse of the heart, is showing us his ruin, through what happened to the object of his love. It’s a dizzying array of perspectives and modes of time.

The next album to do this and what I believe to be his best work since then is “Time Out of Mind.” 22 years after that first marital estrangement, Dylan nearly died from histoplasmosis pericarditis, a fungal infection that in rare cases affects — of course — the heart. Again, after frantic touring, he is hospitalized and forced to stay home. This album, his 30th, is a different kind of reckoning: this time it is with death.

The two are conflated and the album begins with “Love Sick.” I see lovers in the meadow/ I see, I see silhouettes in the window/ I watch them ‘til they’re gone/ And they leave me hangin’ on/To a shadow/ I’m sick of love Sick of love, sick from love, sick in the heart. The speaker watches new love in real time and at the same time sees the past is gone. We get the conflation of time again and the uniting of subject and object. Everything is haunted.

Songs like “Standing the Doorway” (“Everything was going too fast, today it’s moving too slow… I got no place left to turn, I got nothing left to burn.”) “Not Dark Yet” (“But it’s getting there…”): “Make You Feel My Love.” (“The storms are raging on the rolling sea/And on the highway of regret/The winds of change are blowing wild and free/ You ain’t seen nothing like me yet.”).

Slow down an anthem and it becomes a love song. That’s a different kind of collective power, in any genre. These are the most emotionally truthful albums Dylan has written. That “Time Out of Mind” lands last on “Highlands,” a blues riff clocking in at over 16 minutes, serves as dodge and cover. The tone shifts and the narrative distance between speaker and listener is vast, but the devastation is the same:

My heart’s in the Highlands, can’t see any other way to go/Every day is the same thing, out the door/Feel further away than ever before/Some things in life it just gets too late to learn/Well I’m lost somewhere, I must have made a few bad turns.

There’s no chorus or a bridge. You cannot sing along until you listen. A lot.

What strikes me 23 years after the album’s release, is that when he nearly died, Dylan was only 56, which then seemed ancient, as far into the future as I might see. “Time out of Mind” is one of the first Dylan albums I listened to when it was released. I gave it to myself. It’s only as I write this that I realize that only two years previously I had an illness I nearly died from. I had my own reckonings, far too soon.

As with all art, perhaps it is less about an objective “best” (has there been a woman to consistently review Dylan or will men be explaining Dylan to me into eternity?) and more about where we are in relation to the material.

“Rough and Rowdy Ways” comes again out of a period of respite for Dylan, and indeed, for the world. We are isolated and aching and we are listening. That does not make it the best album since “Blood on the Tracks” but it makes it the most imperative one since “The Times They Are a Changing.” The single, “Murder Most Foul,” was released on March 27th, 2020, at the relative beginning of our collective isolation. It felt so wonderful to have him, briefly, back again. President Kennedy assassination? OK, a story about the past to examine the present. Nearly 17 minutes long? Dodge and Cover. References? Let me get out my decoder. I can see clearly. All the links. To history and aging and the near far past. It’s all gone. It’s a clear and painful line. I see the allusions and the sadness and the management of legacy. I am reading again. I have so much to say. It’s spoken word and I’m listening. It’s less vulnerable and raw than tired and wise but I know that all of our flawed heroes, our cruel mentors, they’ll be gone soon. Say goodbye. Let them say goodbye.

Jennifer is the author of three novels for adults and two for teens. Her novel “The Mothers” is currently being adapted to film. She’s an associate professor at Lafayette College.