Books Briefing: A mysterious postcard illuminates a French family’s Holocaust history

Plus doppelgänger stories, new Jewish romance and a reboot of a Yiddish classic in this month’s books newsletter

Photo by iStock

This is Books Briefing, your monthly tour of the Jewish literary landscape. I’m a culture writer at the Forward, and I spend lots of time combing through new releases so you can read the best books out there. If you’d like to receive this dispatch in your inbox, sign up for the Books Briefing newsletter here. You can also shop this newsletter by visiting the Forward’s Bookshop storefront. (If you shop from our page, the Forward will earn a small commission.)

Jewish author Rafael Frumkin is not a con artist. (At least, I don’t think he is.) But in his novel Confidence, he shows he’s really good at coming up with scams.

Ezra, the novel’s sly and unprepossessing protagonist, starts out hawking knock-off Adidas sneakers and fake cocaine (ground-up Sudafed and sea salt, if you’re wondering) to his high school classmates. After falling in love with Orson, another incipient con artist, he moves on to bigger prey, creating bogus online companies and seducing women in order to swindle them.

Sometimes lovers, sometimes friends, Ezra and Orson share an appetite for grift that leads them to the upper echelons of Silicon Valley, where they peddle “wellness” technology that’s about as effective as Elizabeth Holmes’ blood tests. But Frumkin isn’t just trying to dazzle readers with inventive schemes. An excellent pick for anyone who knows a little too much about Caroline Calloway, Confidence asks if the American ideal of success and prosperity under capitalism isn’t the biggest scam of all.

Frumkin, who published his first novel, The Comedown, in 2018, teaches at Southern Illinois University. I Zoomed with him to talk about writing routines, pandemic-era epiphanies, and (not) reading contemporary fiction.

What does your writing routine look like? Unfortunately, my writing happens in fits and starts. I’ve tried to have a daily routine and do everything the right way, but it hasn’t worked. I write when I’m inspired to write and I don’t write when I’m not inspired. My writing usually takes place in these huge bursts, and then I won’t write for a few months. At the times when I am writing, I usually get up, make tea, and write as soon as I’ve walked the dog and fed the cats.

Has the pandemic changed the way you write? The pandemic really gave me an excuse to hunker down and write. I was fearing for my mortality like we all were. And I was like, if I die of COVID, what do I want to be remembered for? How do I want to spend my time when I have so much free time on my hands? And when I’m not seeing other people, how can I imagine myself into situations that are more socially rich and engaging than the one I’m in? It gave me the opportunity to get extremely serious about the writing goals I’d set for myself.

What do you do to wind down? I’ve gotten to the point in my life where I have to read older books in order to read for enjoyment. I love contemporary fiction, but I read it like, “Oh, here’s a cool craft thing they’re doing. Here’s this and this and this.” I’m reading as a writer. Some of the old school inimitable stuff I’ll read for enjoyment, because it’s not of the same era I’m in and I can’t even replicate it. You can’t replicate Italo Calvino or Thomas Mann.

You teach at Southern Illinois University. What are your favorite texts to teach students? I have a really fun time teaching Karen Russell. I taught Orange World this semester and it was great. Speaking of Calvino, I’m teaching Cosmicomics; those stories are gorgeous and the students respond to them so well. I teach a lot of Zadie Smith, Jhumpa Lahiri, Colson Whitehead. Basically, with the exception of Calvino, Gen X giants of literary fiction. I try to focus on what fiction has been doing in the past 10 to 15 years.

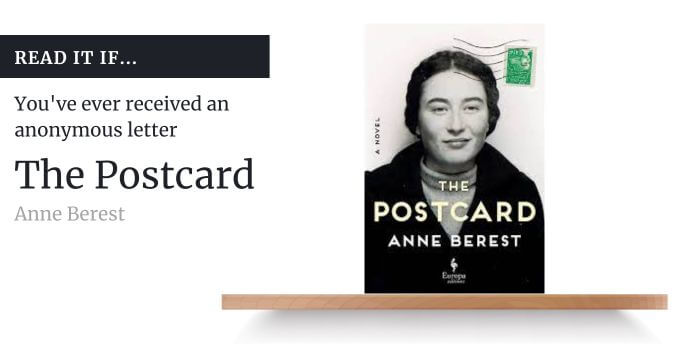

The French writer Anne Berest grew up without knowing much about her family. Her grandmother, Myriam, lost her parents and two siblings to Auschwitz and refused to talk about them after the war. Berest’s mother, Lélia, inherited that reserve even as she started to research the family’s Holocaust history. Berest only becomes truly interested in her family tree when she herself becomes pregnant with her first daughter. In particular, she wants to figure out the origins of a mysterious postcard that Lélia received in 2003, on which an unknown writer has scrawled the names of the family’s murdered ancestors: Ephraim, Emma, Noémie, and Jacques.

Not quite a memoir and not quite a novel, The Postcard chronicles Berest’s quest to both piece together the history Myriam never wanted to discuss and find the sender of the postcard. Tracing Lélia’s decades of archival research and following Berest to private detectives and handwriting analysts, the book sometimes resembles investigative journalism. At other times, Berest uses bureaucratic records and family stories as a launchpad into fictionalized accounts of the family’s past in which she takes on the perspective of her grandmother and her murdered relatives.

A critical darling when first published in French in 2021 and an absolute page-turner as translated by Tina Kover, The Postcard is most original when exploring how France’s cultural amnesia about its Holocaust history shapes the lives of its Jewish citizens generations later. Berest addresses this question via her more observant boyfriend Georges, whose friends are always willing to discuss the state of French Jewry over dinner. All of them are educated, assimilated, and consider themselves completely French. (So will any American reader: The women in this novel amply prove their Frenchness by chain smoking without getting lung cancer and effortlessly fitting into cocktail dresses they bought before having children.)

But disturbing incidents — swastikas scrawled on Jewish houses, arson attempts at synagogue, antisemitic comments lobbed on the playground — serve as reminders that France considers them primarily Jewish. “When I read the papers, when I see everything that’s going on in France nowadays, it seems to me that people just want us to disappear,” one friend says at a Passover Seder.

Berest’s genre-straddling approach isn’t without flaws. Because the present-day detective story is so interesting, the novelized portions of The Postcard can feel thin by comparison — the dialogue at Georges’ dinner parties reads more like the transcript of a political focus group than an organic conversation between friends — and the problem of distinguishing between the book’s real and imagined elements can be distracting. But these bumps in the narrative road lead back to one of the novel’s central questions: What does the work of Holocaust memory look like when most survivors and perpetrators have taken their secrets to the grave? Berest has found one method of telling a story that belongs equally to her ancestors and to her. (And if you want to read more on the state of the contemporary Holocaust memoir, I recently wrote about a wave of family histories written by the descendants of perpetrators.)

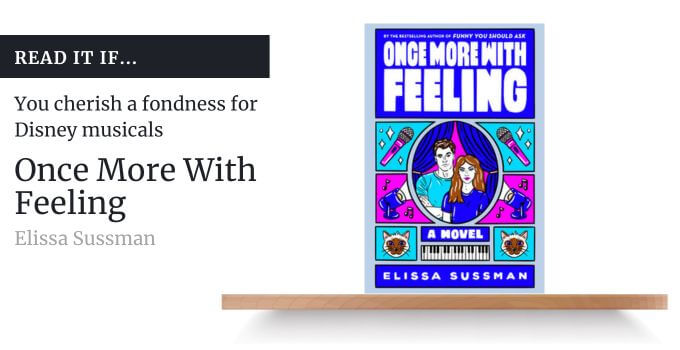

Jewish romance novelist Elissa Sussman’s latest novel seems specifically targeted at millennials whose first experience of romance arrived via late-2000s made-for-TV singing dramas. If you’ve been following the blossoming trend of Jewish romance novels and still remember the first time you heard Zac Efron sing “When There Was Me And You” in High School Musical, this one’s for you. Kathleen Rosenberg, was once a teen pop star beloved for her auto-tuned voice and spicy romance with Ryan, a member of the One Direction-esque boy band CrushZone. (Typing the word “CrushZone” does make me a little ill. But you, dear reader, won’t have to worry about that.)

When she falls for Cal, another CrushZone (argh!) member, and ditches Ryan, the tabloids come for her a la Britney Spears and her singing career collapses. Now, Kathleen is a self-actualized 30-something dance teacher who wants nothing to do with boy bands — until Cal resurfaces, inviting her to star in a Broadway show he’s directing. Finally, Kathleen can live out her creative dreams; but she has to work with a man who watched her get pilloried in the press without suffering any of the fallout.

I enjoyed Once More With Feeling for obvious reasons. (The reasons: I remember the first time I heard Zac Efron sing “When There Was Me and You.”) But I especially appreciated the way it draws on the very real late-aughts culture of celebrity witch hunts, which I watched alongside High School Musical but didn’t yet recognize as ghoulishly sexist. Without sacrificing the bubbly optimism of a rom-com, Sussman imagines what recovery and repair from early 2000s tabloid culture might look like for the women — popstar or plebeian — who grew up shaped by it.

In the opening of Deborah Levy’s latest novel, our heroine Elsa experiences a stock nightmare: A world-famous pianist, she freezes up while playing Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2, flubbing a concert in front of an audience of thousands. Fortunately for me, I am a mediocre pianist and will never experience this in real life. Unfortunately for Elsa, her image and career are in jeopardy.

To recover from what she slowly realizes is a psychic break, she retreats to Athens, where she sees a woman she believes is her doppelgänger. As Elsa travels around Europe, visiting friends and giving private lessons to the talented children of extremely dysfunctional parents (the best parts of the novel, by far), the doppelgänger follows her, seeming to offer clues about Elsa’s mysterious parentage and difficult childhood but always remaining out of reach. What will it take for Elsa to regain her sense of self, her confidence as a musician? Surprisingly, the answer does not involve losing her doppelgänger.

I came to Deborah Levy through her erudite and thoughtful memoirs about unpartnered middle age. While her nonfiction carefully parses the political implications of modern domestic life, her novels are far less tied to realism. If you can’t deal with a few otherworldly characters and/or need endings to make immediate sense, August Blue is not for you. I had to relax my internal vise grip on conventional narrative to slip into this story. Once I did, I loved being inside Elsa’s mind.

If you joined the Forward’s book club in the early days of the pandemic, you might be familiar with Bread Givers. If not, this underrated classic, first published in 1925, may have passed you by — but Yezierska’s novel has returned to print in a new edition from Penguin Classics, with a somewhat freaky cover that gestures at the extremely unpicturesque nature of this coming-to-America tale.

Sara Smolinsky is a shtetl-born child who immigrates to the Lower East Side with her family. Since her father, a devout rabbi who has dedicated himself to studying Torah, refuses to work, Sara and her three sisters provide for the family, while their mother vacillates between adoration of her husband’s religiosity and anger at his selfishness. Growing up in this fraught environment, Sara takes a grim view of the lot of Jewish women. Describing the traditional belief that only men can gain entrance to heaven through Torah study, she remarks dryly, “Only if they cooked for the men, and washed for the men, and didn’t nag or curse the men out of their homes … then, maybe, they could push themselves into Heaven with the men, to wait on them there.”

A budding writer by the end of the novel (shocker!), Sara struggles to maintain her identity as a Jew without dooming herself to a life of thankless servitude like her mother’s, and to establish her right to a creative life in a society that views women as accessories to their husbands. Bread Givers avoids easy parables about immigrants within American culture and women within Jewish culture. Sara wins her independence with such difficulty, and experiences so much loneliness in the process, that she often wonders if it’s worth the fight. As a reader, so did I.