How Isaac Bashevis Singer’s translator edits without editing

David Stromberg, the Yiddishist behind a new collection of the Nobel Prize winner’s essays for the Forward, talks about the challenges of bringing his work to a modern audience

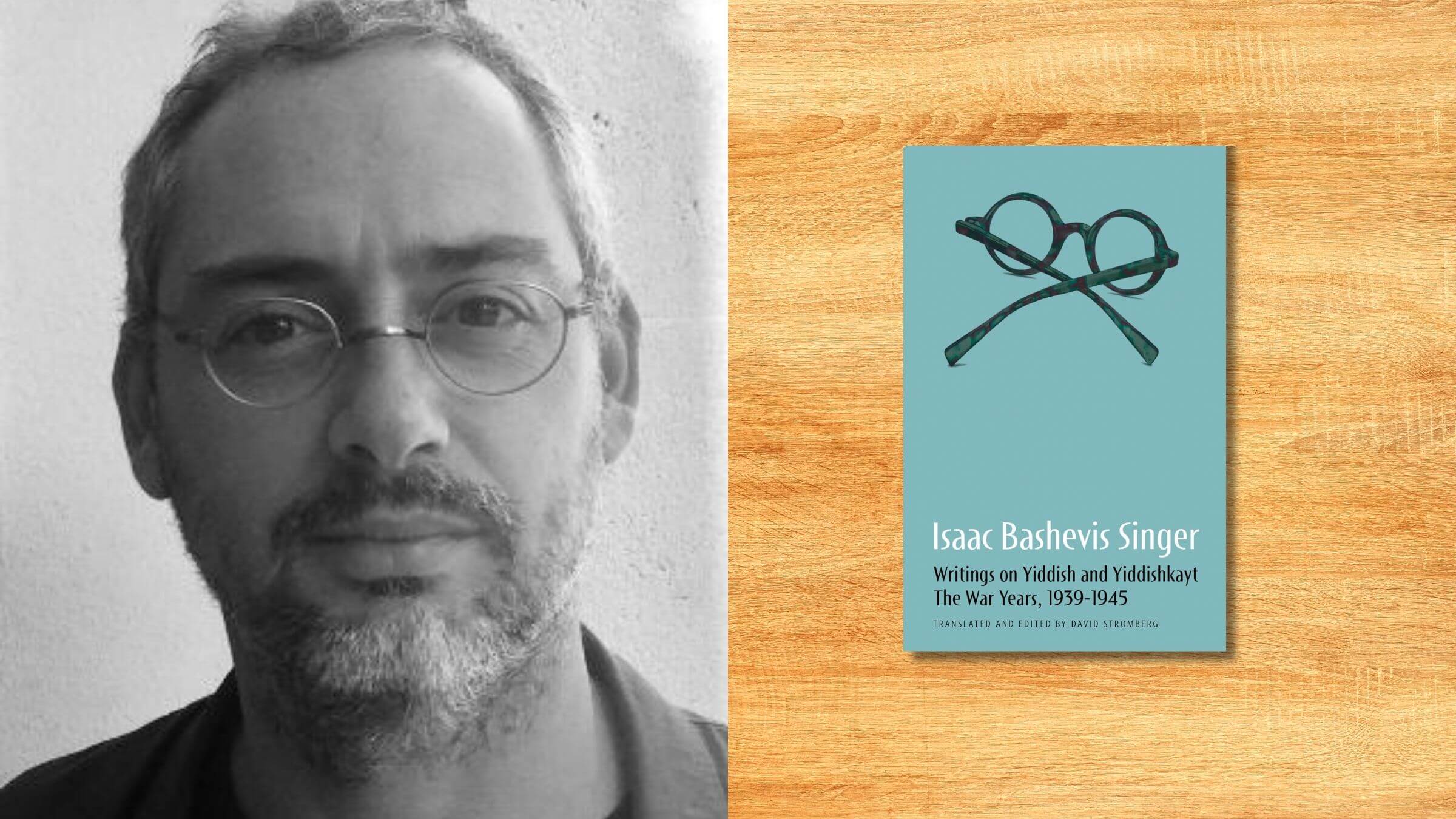

David Stromberg is the translator of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s journalism for the Forverts Photo by White Goat Press, David Stromberg

Readers of the Yiddish Forverts in the 1940s would have been familiar with the contributors Yitskhok Bashevis, Yitskhok Varshavski and D. Segal, whose bylines appeared frequently atop articles that chronicled Yiddish history and folklore, mourned the destruction of Jewish communities in Europe and examined the changes in Jewish communal life that immigration to the United States had wrought.

What they might not have known — at least, not for a few more decades — was that one man lay behind all these pseudonyms. The Polish-born Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer would eventually win the 1978 Nobel Prize in Literature for a body of work that included the epic novel The Family Moskat, published serially in the Forverts. Compared to his fiction, Singer’s work as a journalist often gets short shrift. But translator David Stromberg argues that the writer’s output as a newspaper contributor is inseparable from his later books.

In his collection of Singer’s translated essays, Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkeit: The War Years, 1939-1945, Stromberg presents selections from Singer’s Forverts oeuvre alongside commentary on his development as a writer, as well as the shifts in his perspective that occurred as he gradually became aware of the Holocaust unfolding in Europe.

I spoke with Stromberg about Singer’s approach to writing about Europe for an audience of American Jews, his shifting perspective on Israel and the unique challenges of editing a multilingual writer who often did his own translations.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you first become interested in Bashevis Singer’s work for the Forverts?

I wrote my doctorate on Dostoevsky, Camus and Singer, and noticed that all of them had worked and published in newspapers. The connection between newspaper writing and high literature interested me, particularly as Singer and Camus were both Nobel Prize winners. I was curious whether the presumed hierarchies between high and low writing were somewhat false. With Bashevis, you couldn’t separate the immediacy of his publication in newspapers from the eventual publication of his writing in other venues.

Say more about that.

After his first years at the Forverts, when he did write stories and publish a novel serially, Singer wrote an anonymous column for several years, almost until the articles that start this collection. What happened there is the beginning of a process in which he learned that he needed to understand the psychology, context and background of his readers, and to give them what they need in a way they can understand.

When he was in Poland, if he wrote about certain villages, he assumed that most readers would know what he’s talking about. They knew the places, the geography, the weather — a lot of information beyond what’s on the page. In America, when he said the name of a Polish village, nobody knew what he was talking about, even if they could read every single word in Yiddish. There’s a shock, in the 1935 and 1936 pieces, when he comes to realize that although he has Yiddish-speaking readers, none of the intended information is getting across to them.

When Singer came back to the Forverts in 1939 as Yitzhak Varshavski, the newspaper was the medium by which he developed a relationship with readers. He started by publishing a series of articles on lesser-known historical figures, who would have been much more familiar to people in Poland. And he developed a knack for giving information — about towns, customs, ways of dress — without explaining things. It doesn’t sound like he’s speaking in a didactic or pedagogical manner, but there is that aspect to it.

What was the editing process like?

When I was thinking about how to edit the pieces down, I learned from Bashevis’ idea that you have to be aware of your audience and your readers. I tried to apply a similar editorial approach, taking into account that readers are reading a collected book, not just one article. If I were sending you an article just to read, I might keep more detail, but if I make a decision to keep a particular level of detail or an example that he gives in one article, then I have to apply this to the other articles to be consistent. Then I run the danger of overwhelming readers with detail that makes it harder to get at the main themes.

Editing is also a performative act. As with writing, the decisions are sometimes intuitive or spontaneous. You make them based on a lot of background knowledge, but you deploy that knowledge in real time.

Is this level of editing common in translations or reissues of Singer’s work?

Unfortunately not. I say “unfortunately” because I’m doing this after having studied Singer’s own editing, going over his own edits of his own essays and lectures and the kinds of cuts he would make. Having read some of his correspondence, I saw letters that he received from his editors and understood just how big a role revision and rewriting had in his material. He was a master editor. I don’t rewrite anything, so it’s a little more tricky for me. I have to give the impression that the text is as polished as his rewritten work, but only by taking out text.

When Joseph Sherman, a very dedicated Bashevis scholar, translated Shadows on the Hudson, he took an extremely literalist approach. He wrote a whole article about his experience with Singer’s editors at FSG, who encouraged him to take Singer’s own editorial process into account in his translation, and he refused. Even though that novel still holds up, the translation opened it up to the criticism of, “Oh, it was published in the newspaper, and there’s a lot of repetition.” If you’re taking only Singer’s writing into account and not his revising and editing, you’re essentially leaving out half the artist.

Does this controversy over how to translate him stem from the fact that he translated a lot of his own work into English during his lifetime?

The idea that he translated himself is one that he fought against. The public image of the translated author gave him a particular patina that was important to getting his message across. Whereas in reality — I found this on a voice recording — someone asked if he had translators, and he said, “Well, I do most of the translation myself, but I need help putting the sentences together.” Essentially, his syntax wasn’t great.

What do you mean when you say the image of the translated writer gave him a “patina?”

Bashevis emerged as a storyteller from the old world. This wasn’t just accidental; I think he understood that this was the role in which he could get his larger mission across, and so he emphasized it. Part of that was having the mystique of being a translated author.

So it would have harmed his credibility as a voice from the old country if he were known to be translating his own work?

I don’t think it would have harmed his credibility. I think it would have distracted from the main point, which was that the work was written by someone who had lived there.

Google Alf, the sitcom character. Alf speaks like a New Yorker, but he looks like an alien life form. If Alf weren’t a puppet, and appeared as the actor playing him, it would take away the purpose. You would lose access to this feeling of getting wisdom from the alien life form. I think it’s not an accident that only later, when he won the Nobel Prize, did he start taking full credit for his translation. By then, he was already established.

What shifts did you observe in Singer’s perspective as he started to receive more reports of the Holocaust unfolding in Europe?

There was separation between American Yiddish readers and English readers, which was that the events and the extent of the Holocaust were much more clear to the Yiddish-speaking world very early. By 1941, when Eichmann was transferred to Latvia and Lithuania, that was a headline piece in the Forward; they called him a “special Haman.”

What began in 1939 as a desire to convey Jewish spiritual content, history and cultural treasures just became very urgent. For example, the piece cataloging Jewish names and Yiddish names: Singer knows that he’s probably the only person interested in modern literary fiction who is reading books about names. So he’s got to get it down on record, because if he writes about it now, then he knows that tomorrow at least X number of readers will know about this. Then, of course, he’s done his own taxonomy of Yiddish names for the rest of his career when he gives names to his characters. So he’s saving the existence of these books, he’s showing readers during the Holocaust the kinds of histories Yiddish names have, and he’s laying the groundwork for his own fiction.

I was really moved by this kind of cataloging, as you put it. There’s a piece about the different streets in Jewish Warsaw, and how hard it is to imagine them rid of all the Jews, that, to me, drove home the difference between his viewpoint and the perspective of a modern reader who might find it equally hard to imagine a Jewish community existing in Warsaw.

Nobody could have imagined the success of such a destruction, but you’re also talking about people who lived through WWI. Human destruction systematically aimed at Jews hadn’t been with him his whole life, but unprecedented human loss, as well as complete disintegration of political, governmental, and social orders, were things Singer had known since he was a teenager. This was someone who watched kingdoms and empires collapse into nation-states, which then collapsed into civil wars, which then collapsed into antisemitisms. So there’s a way of harnessing the level of destruction you have witnessed into an intuitive sense of how much worse things can get.

There are a couple essays in this collection on the theme of Jewish “powerlessness,” and one in which Singer suggests that resistance to demagoguery is an essential characteristic of Yiddishkeit. Those essays read quite differently in a moment when there is a very powerful Jewish state, and many Jews consider the leaders of that state to be demagogues. What do you think these essays can offer readers today?

Bashevis didn’t lack criticism for the kind of corruption of rabbis. But even if you follow a rabbi who has a particular level of power, there are by nature so many of them that there’s a decentralized structure to Judaism as a whole.

When we’re looking at the situation today, we have to resist falling for the impression that the current leaders in power are giving us, which is that they are the only leaders: Only this group can lead us, only this man can keep us safe. Wherever they live, Jews can see this as a reminder that there’s a difference between power and centralized power. What we’re witnessing today in Israel is the result of years of manipulation and centralization of political power. But it’s not social power, and it’s not the power of civil society. So there’s a limit to how much it can achieve, because the fabric of Jewish culture and history is always multiple. No leader can completely tear that fabric apart.