Nazi collaborator monuments in Bosnia and Herzegovina

One city renamed multiple streets in July 2022, others remain

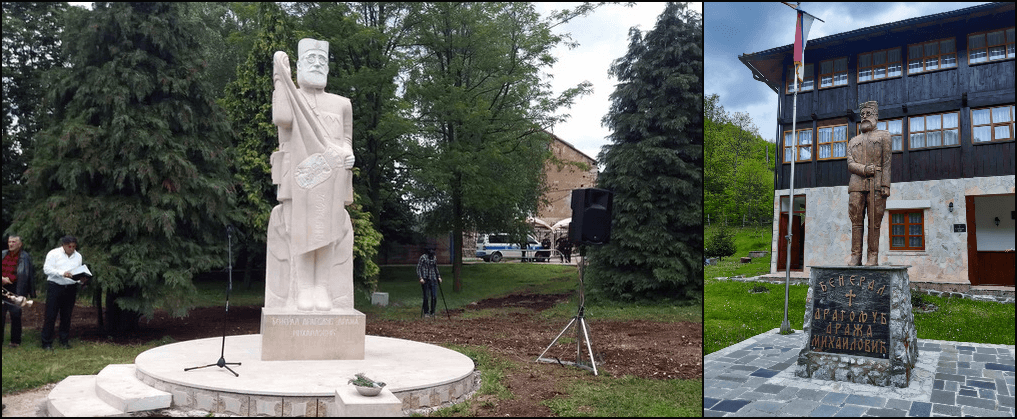

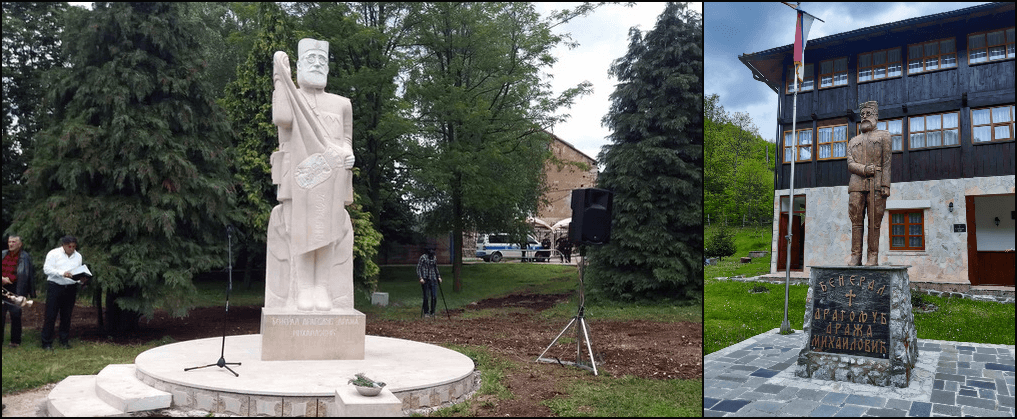

Left: Dragoljub “Draža” Mihailović monument, Bileća (Sarajevo Times). Right: Mihailović monument in Dobrunska Rijeca (Wikimedia Commons). Image by Lev Golinkin

This list is part of an ongoing investigative project the Forward first published in January 2021 documenting hundreds of monuments around the world to people involved in the Holocaust. We are continuing to update each country’s list; if you know of any not included here, or of statues that have been removed or streets renamed, please email [email protected], subject line: Nazi monument project.

Sarajevo — Bosnia’s capital has a school and a street named after Mustafa Busuladžić (1914–1945), a supporter of Croatia’s fascist Ustasha and virulent antisemite who cheered on the extermination of Bosnia’s Jews. In 1942, Busuladžić conducted a fawning interview of Amin al-Husseini, notorious Hitler ally who recruited Muslim soldiers for the SS.

Busuladžić’s antisemitism was so toxic that the 2016 decision to honor him with a school drew rare public condemnations from the U.S. embassy and the Israeli government. In 2018, Sarajevo authorities voted to change the name, yet the decision was on paper only; the school remains named after Busuladžić. That’s common in Eastern Europe — often, even after promising to remove names of fascists and antisemites, local authorities don’t follow up. See reports by Radio Free Europe and Balkan Insight.

For a fantastic overview on Bosnian streets named after both Croatian and Serbian Nazi collaborators, see Selma Boračić-Mršo’s coverage in Radio Slobodna Evropa, Radio Free Europe’s Balkan branch; Google translation here. (Many thanks to Rory Yeomans for generously sharing his encyclopedic knowledge of Balkan events and collaborators.)

Sarajevo and Goražde — Sarajevo has a street named after Husein Đozo (1912–1982), Waffen-Hauptsturmführer in the 13th Waffen Mountain Division of the SS “Handschar” (1st Croatian) where he served as imam and political educator of the troops. He also has a school in Goražde.

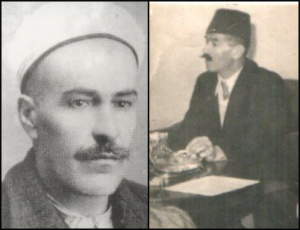

Above left, Đozo (middle) with a German officer (left) and prominent Hitler ally Amin al-Husseini (right). Above right, Handschar soldiers study a brochure on “Islam and Jews.”

Sarajevo — The capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina also has a street honoring Muhamed Pandža, who died in 1962, a Bosnian religious leader who was a prominent advocate of both Nazi Germany and its ally, Croatia’s fascist Ustasha. Pandža worked hard to recruit Muslim soldiers for the Waffen-SS Handschar division.

Above right is a photo of Handshar volunteers, 1943. Note the Totenkopf (skull-and-crossbones) badges on the fezzes: this SS symbol is widely used by today’s neo-Nazis. The right collar patches, which are blurry in the photo, contain swastikas.

Update (July 2022): In July 2022, the Mostar City Council voted to rename all streets in this entry.

Mostar — The largest city in Herzegovina was teeming with streets named after Croatian fascists. These included Mile Budak (1889–1945), Ante Vokić (1909–1945) and Mladen Lorković (1909–1945), ministers in Croatia’s Nazi-allied Ustasha government. These individuals were not only Third Reich allies but propagandists and inciters of genocide in their own right — in a 1941 rally Lorković proclaimed that the Ustasha’s goal was to “cleanse itself of all those elements that are the misfortune of the nation, that drain healthy forces in our nation. These are our Serbs and Jews.” By the end of the war, the Ustasha had exterminated hundreds of thousands of Serbs, Jews and Roma.

Mostar also has a street named after Jure Francetić (1912–1942), commander of Ustasha’s infamous Black Legion which carried out massacres of Serbs and Jews across Bosnia (above right). See report from Deutsche Welle (Google translation here). Above left is a photo of Francetić (center) and Lorković (right) after the conclusion of a counter-insurgency operation in 1942. (Thanks to Faruk Vele of Radio Sarajevo for the street image.)

After the City Council’s July 2022 vote, Mile Budak Street is now Aleksa Šantić Street (in honor of the hometown poet); Vokić Lorković Street, which jointly honored Ante Vokić and Mladen Lorković, is now Tin Ujević Street (also in honor of one of the most seminal poets of modern Croatia); and Jure Francetić Street is now Humska Street. The renamings were welcomed by the U.S. and Israeli ambassadors to Bosnia as well as the European Union. See coverage by Sarajevo Times.

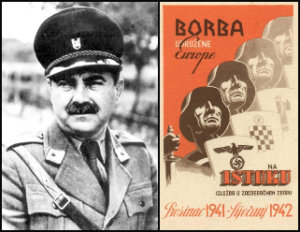

Čapljina — Yet another town with a street for Mile Budak, leading Ustasha ideologue and minister of education whose fanaticism inspired the persecution and murder of Jews, Serbs and Roma. Above right is a 1941 Ustasha recruitment poster portraying Croatia alongside Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy in “the struggle of a united Europe.”

Banja Luka and Mrkonjić Grad— On Mount Čemernica, near the city of Banja Luka, is a memorial to Lazar Tešanović, who died in 1947, while Banja Luka itself has streets named after Uroš Drenović (1911–1944) and Rade Radić (1890–1946). All three were commanders of the Chetniks, the Serbian nationalist militia which collaborated with the Nazis. Uroš Drenović has an additional street in Mrkonjić Grad. Banja Luka also has a street for Dragomir “Dragiša” Vasić (1885–1945), another Chetnik commander. Coverage in Radio Slobodna Evropa (Radio Free Europe’s Balkan branch; Google translation here).

In 1942, Tešanović, Drenović and Radić entered into an alliance with Croatia’s genocidal Ustasha regime, which was also allied with the Nazis. The Serbian nationalist Chetniks and the Croatian nationalist Ustasha hated and slaughtered each other. Their unlikely alliance took place because of a common enemy — Yugoslavia’s Communist partisans, who were gaining ground against both Chetniks and Ustasha. Above left, Drenović (far left) with Ustasha fighters in 1942; above right is Vasić street. (Thanks to Milica Pralica of Oštra Nula for the street image.)

Bileća and 11 other towns — Republika Srpska, one of the two entities composing Bosnia and Herzegovina, is full of monuments and streets honoring Chetnik leader Dragoljub “Draža” Mihailović (1893–1946). Examples include: a monument and square in Bileća (above left), Dobrunska Rijeka (above right, Google translation here), Bijeljina (Google translation here) and Brčko; a square in Ugljevic; and streets in Brod, Derventa, Gradiška, Lukavica, Rogatica, Rudo and Šamac. (Thanks to Sarajevo Times for the Bileća monument image.)

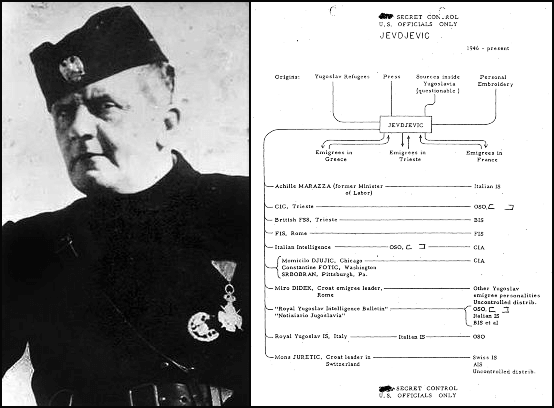

Pale (entry added January 2022) – A street named for Dobroslav Jevđević (1865–1962), another Chetnik commander who collaborated with fascist Italy. In October 1942, Jevđević’s forces participated in Operation Alfa, an Italian-led offensive in Herzegovina. In the wake of the offensive, his men carried out a series of massacres, killing at least 500 (some sources have much higher casualty figures) Catholics and Muslims. Jevđević’s record is varied: at one point he denounced the Chetniks’ killing of Croats; another time, he issued an antisemitic proclamation claiming the ranks of Yugoslav Partisans were filled with Jews. After the war, Jevđević lived in Rome where he worked with several Western intelligence services, a common Cold War occupation for Nazi collaborators from Eastern Europe. Above right, a CIA chart detailing the intelligence network created by Jevđević.

Doboj (entry added January 2022) – This town has a street to Chetnik commander Cvijetin Todić (1910–1947). In 1942, Todić, along with Lazar Tešanović and other Chetnik commanders, entered into an alliance with the fascist Ustasha, allies of Nazi Germany (see Banja Luka entry above). Above, Chetnik and Ustasha fighters, date unknown.

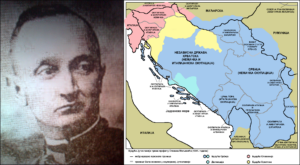

Banja Luka (entry added January 2022) – A street named for Stevan Moljević (1888–1959), Chetnik ideologue and executive member of the Central National Committee, an advisory body of the Chetnik movement. In 1941, Moljević authored a tract titled Homogenous Serbia which called for the expansion of Serbia’s borders in order to create a “Greater Serbia,” one which would be populated solely by ethnic Serbs. (Above right is a map illustrating Moljević’s vision.) While there’s no direct link between this tract and ethnic cleansing, the concept of a nation not being able to survive without the establishment of an expanded ethnically homogenous state often inspired WWII massacres in the Balkans and Central Europe. See the Serbia section for another Moljević street.

Čajniče (entry added January 2022) – A street named after Chetnik commander Pavle Đurišić, (1909–1945), who commanded Chetnik troops operating in Montenegro. In the process, he collaborated with the Third Reich, which awarded him the Iron Cross, a Nazi Germany military honor. Above right, an announcement of Đurišić receiving the award in the paper Lovćen, 1944.

Đurišić was also allied with Serbia’s puppet government of Milan Nedić, which aided the Nazi annihilation of Serbian Jews. Additionally, Đurišić had ordered his troops to carry out ethnic cleansing of Muslims in Bosnia and Montenegro. See the U.S. section for a bust of Đurišić near Chicago.

Grude (entry added January 2022) – A street to Rafael “Ranko” Boban (1907 – disappeared 1945), commander of the Black Legion. This infamous unit in the Croatian Ustasha forces carried out widespread massacres of thousands of Bosnian Serbs and Jews. Boban vanished in 1945, leaving various theories about his fate. Above left, Boban (on right), 1943; above right, the Black Legion, 1942.

Note: Mostar also had a street named for Boban until July 2022, when the City Council voted to rename it Fr. Ljudevit Lasta Street, in honor of a celebrated Mostar priest who worked with war wounded and local hospitals (Google translation here). See above for more details.

Sarajevo (entry added January 2022) – Bosnia’s capital has streets named after Sulejman Pačariz (1900–1945) and Osman Rastoder (1882–1946). Both men were religious and military leaders; both commanded units in the Sandžak Muslim militia, a paramilitary formation which fought under the Ustashe, then Italy and then Nazi Germany.

In 1943, Pačariz’ unit was transferred to the newly-formed SS Polizei-Selbstschutz-Regiment Sandschak, a “self-defense” police regiment within the SS. Pačariz, above right, was the regiment’s commander.

For more monuments glorifying Balkan Nazi collaborators, see the Croatia, Serbia, U.K., U.S., Canada and Australia sections.