Three Cities of Yiddish: St. Petersburg—Warsaw—Moscow

This article originally appeared in the Yiddish Forverts.

Three Cities of Yiddish: St. Petersburg—Warsaw—Moscow.

Edited by Gennady Estraikh and Mikhail Krutikov.

Oxford: Legenda, 2017, 201 pages

The British book series “Studies in Yiddish,” published by Legenda (and known among academics as “the Legenda series”), is in my estimation the most important venue for contemporary research on Yiddish literature and culture in the world today. Established at the end of the 1990s by the late Joseph Sherman, the series is all that remains of a once vital center for Yiddish research and pedagogy in Oxford University. Over the course of the series its current editors, Gennady Estraikh and Mikhail Krutikov (both of whom were affiliated with Oxford two decades ago, and who had met previously amidst the final vestiges of Yiddish culture in the Soviet Union), have made leading contributions — and in some instances the only contribution — to the research of individuals such as Dovid Bergelson (Volume 6), Peretz Markish (Volume 9), and Joseph Opatoshu (Volume 11), as well as more general themes such as Yiddish and the Left (Volume 3), Yiddish in Weimar Berlin (Volume 8), and children’s literature in Yiddish (Volume 14).

The most recent volume in the series is “Three Cities of Yiddish,” which takes its name from a novel written by Sholem Asch, first published serially in the Forward between the years 1927-1932. The title of the collection is a bit surprising, though. To begin with, although Asch’s novel is known as “Three Cities” in English, its Yiddish title is “Farn Mabl” (Before the Deluge), so the reference is apparently intended more for readers of English than of Yiddish. In total candor, it’s hard for me to understand why one would choose Asch’s overblown melodrama as a model for a collection about Yiddish culture.

Secondly, when one considers the questions of urbanization and Yiddish culture, which is, in fact, a significant and under-considered theme, Petersburg, Moscow, and Warsaw would hardly be the first cities on which to focus. Why not Odessa, Kiev, and Vilna? In fact, why has there never been a volume in the series dedicated to New York? Although nearly all of the articles assembled here are worth reading, the volume as a collection lacks a central thesis or argument to connect the perspectives and methodologies of its individual contributions.

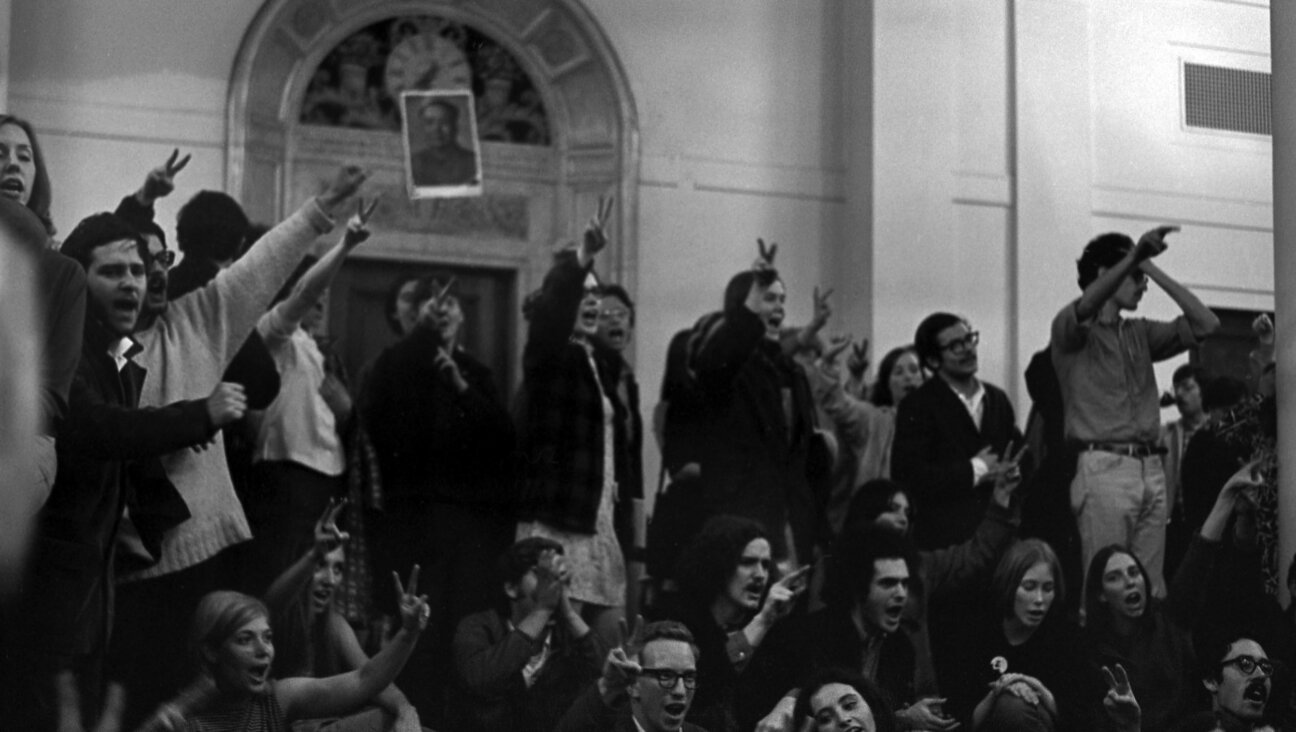

Among the highlights of the book are the articles by Estraikh and Krutikov themselves, each of which underscores the individual talents as well as the mutual interests of the authors which accounts for their distinctively productive collaboration. Estraikh’s article concerns Sholem Asch’s trip to Moscow in 1928, and provides a different facet to the primary concern of his own research: the approach of Yiddish literature, both in the Soviet Union and internationally, to Communism. Most Yiddish writers seemed to fall into a consistent pattern: at first, they are drawn to Communist ideology for idealistic reasons; then they are forced by party dictates to adopt inhumane positions — whether on aesthetic questions, Jewish questions, or even regarding their own friends — and finally, the author becomes disenchanted with the Party and the State, which for writers in the Soviet Union typically occurred too late to save the writer from the regime’s clutches. But Asch was an exceptional case. Asch at the time was the most popular Yiddish writer in the world, better regarded in translation than in the original, and his visit to the Soviet Union was undertaken more as a celebrity, perhaps like Sean Penn visiting Chavez’s Venezuela a decade ago, than as a Yiddish writer or an emigrant from Eastern Europe. Although Estraikh details Asch’s reaction to the visit, as well as his reception among the locals, there is no evidence of a genuine connection between the visitor and his hosts, or that one changed the perspective of the other.

Krutikov’s article is less historical or biographical and more literary-critical in its focus: it deals with the travelogue Hoyptshtet (Capital Cities) of 1934, written by Der Nister (“The Hidden One,” Pihkhes Kahanovitsh, 1884-1950), one of the greatest Soviet-Yiddish writers. The German professor Sabine Koller also contributes an essay in the volume dedicated to Der Nister’s book, which records his impressions of Leningrad, Moscow, and Kharkov upon returning to the Soviet Union after living in Germany during the 1920s. It’s a real delight to see so much attention is devoted to this book, which has been relatively unappreciated in previous considerations of Der Nister, including the volume dedicated to him in the Legenda Series (Volume 12).

Krutikov’s essay is part of a book that he’s been working on about Der Nister’s career in the Soviet Union, and “Hoyptshtet” plays an important role in Der Nister’s development as a loyal devotee of the “socialist realist” aesthetic. As both Koller and Krutikov demonstrate — the former with a focus on echoes of Russian literature to be found in the book, the latter concentrating on descriptions of architecture and social space — the transformation in Der Nister’s style, from an experimental Symbolist to an ideological realist, parallels the transformation of the cities he visits, from symbols of Czarist oppression to expressions of the new Communist vision and destiny.

Though “Hoyptshtet” had been previously overlooked in critical considerations of Der Nister, because it isn’t a work of fiction and because it belongs to neither of the dominant styles characterizing his writing, as an intermediary work it offers many venues for analysis and speculation. Accordingly, it is one of the most interesting works to be considered in terms of the larger theme of the collection: urbanization and Yiddish culture.

It is all the more lamentable, then, that so little attention is devoted in the volume to an overarching thesis that could connect one article to another. The introduction to the collection consists of a mere four pages, and the volume lacks basic references identifying who the article’s authors are, and how their essays relate to larger research projects. One can only wonder, for example, about the article by Alexander Frenkel dedicated to the question “Did Mikhail Epelbaum Study at Warsaw Conservatoire?” (spoiler alert: he didn’t!) Whether he did or he didn’t, what does this question have to do with the transformation of Yiddish culture from the shtetl to the big cities in the first decades of the twentieth century? The fault here lies not in Frenkel’s fine research, but in the absence of a rationale for its inclusion among the other articles in the collection.

The reason for my bluntness is precisely because the Legenda series is so important to contemporary Yiddish research. In fact, there’s no other publication series since the era of the Field of Yiddish collections of a half-century ago (and that series only managed five volumes over the course of 40 years) that has devoted as much care and concentration to Yiddish as has the Legenda series so expectations for each volume are understandably high and demanding. True, reading an article about Yiddish culture, divorced from a larger context or dialogue with other research interests, is relatively commonplace in academic journals today. But currently, a volume created with a genuine affection for Yiddish and an equally expert critical methodology is only conceivable through this series. Hopefully, future volumes will return to the same standards that have made their previous collections a model for research on Yiddish culture.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30