Arthur Laurents: Broadway’s Last Ferocious Man Opens a New Version of ‘West Side Story’

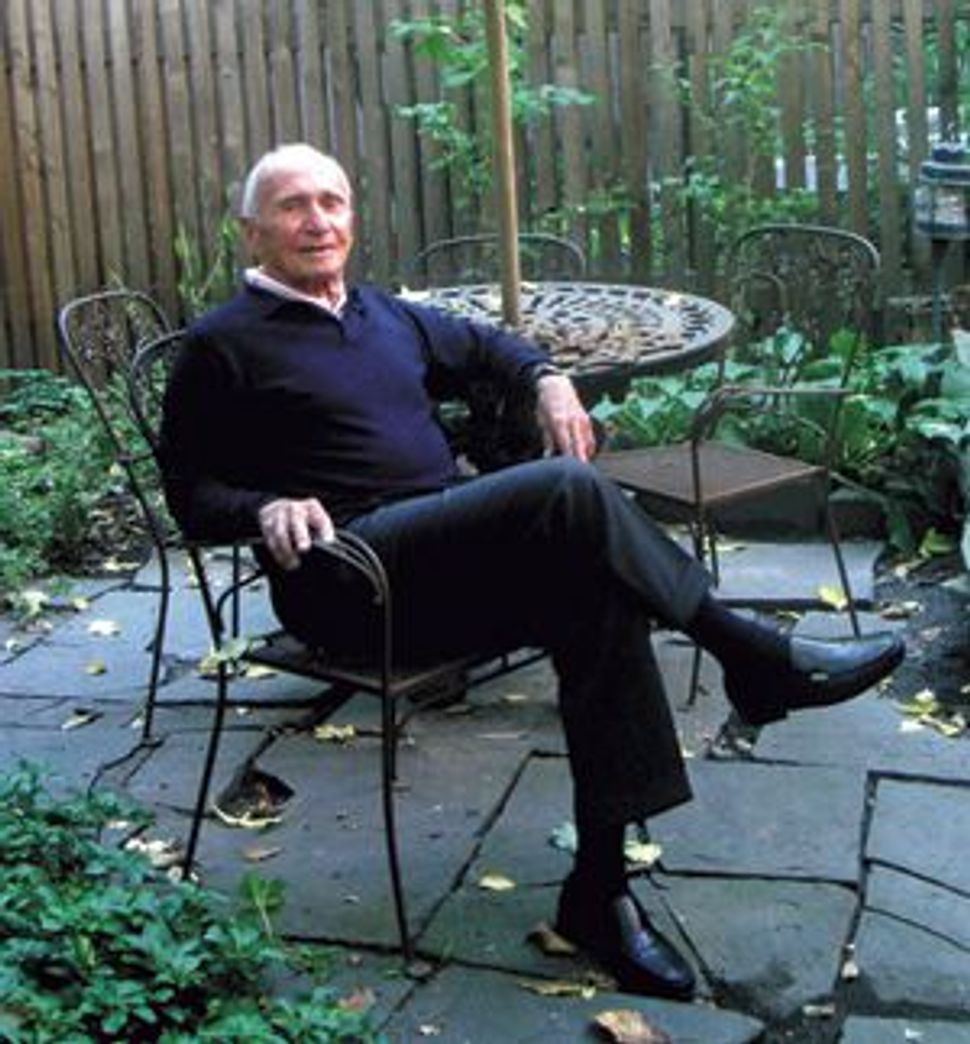

King Arthur: Still reigning over the Broadway stage, including his latest bilingual campaign, ?West Side Story? translated into street smart Spanish by Lin-Manuel Miranda, the Tony Award-winning creator and star of ?In the Heights.? Image by JOYCE RAVID

Jump: A revival of ?West Side Story,? under the direction of Arthur Laurents, opens on Broadway March 19. Image by Joan Marcus

In a showbiz world, where backbiting and hissy fits are a way of life, Arthur Laurents (born Arthur Levine), who has directed a revival of “West Side Story” that opens March 19 on Broadway, stands apart. Laurents, who wrote the original book of “West Side Story,” among many other plays and screenplays, will be 92 on Bastille Day (July 14), but he is no patriarch in the sere and yellow leaf. He has never suffered fools gladly; indeed, in Laurents’s new book, “Mainly on Directing: Gypsy, West Side Story, and Other Musicals” (recently published by Knopf) he takes them by the throat and throttles them until he knocks some sense into their heads.

King Arthur: Still reigning over the Broadway stage, including his latest bilingual campaign, ?West Side Story? translated into street smart Spanish by Lin-Manuel Miranda, the Tony Award-winning creator and star of ?In the Heights.? Image by JOYCE RAVID

Laurents, a native of Brooklyn’s Flatbush area, is a lifelong product of tension and dissent: His father’s parents were Orthodox Jews, while his mother’s Jewish forebears claimed to be atheists. Growing up in a nominally kosher household, Laurents was bar mitzvahed nearly 80 years ago, at which point he left all Jewish religious ritual behind. Yet he has never abandoned his ethnic identity. In 1945, he wrote “Home of the Brave,” a pioneering Broadway drama about Army antisemitism, only to receive a complaint from the Anti-Defamation League that his play was itself antisemitic because its Jewish central character is “neurotic.”

Similarly, Laurents directed and served as script doctor for another Broadway landmark, the 1962 musical “I Can Get It for You Wholesale,” (a vehicle for the 19-year-old Barbra Streisand) about Harry Bogen, a pushy, ruthless garment-industry climber whom Laurents terms, in a reference to Budd Schulberg’s 1941 novel, “What Makes Sammy Run?” a “Sammy Glick cousin.” “There will always be those who say such a character is antisemitic; their number will depend on how successful the show is,” Laurents said.

Clearly, part of Laurents’s brilliance in the theater depends on his determination to evoke reality, regardless of potential offense. Theatergoers marveled last year at the intense intellectual focus and vehement theatricality of his direction of “Gypsy,” in which the Rose of the sometimes wayward Patti LuPone became a Brechtian Mother Courage.

Anyone with this pitch-perfect sense of dramatic verisimilitude may be excused some ill temper when his high standards are not met. “Mainly on Directing” lashes out at length at star British director Sam Mendes, who helmed a previous 2003 Broadway revival of “Gypsy,” for not “having the musical in his bones.” British directors in general irk Laurents, especially when they handle Jewish material like David Leveaux’s 2004 revival of “Fiddler on the Roof,” starring England’s Alfred Molina as Tevye. Laurents called the production “ill-conceived”:

In that new look at an earthy musical, the shabby shtetl where Jews struggled to survive was a polished hardwood floor and a grove of beautiful birch trees with a full orchestra at one side…. Why would any Jew want to leave? Perhaps because none of the residents were Jews… Tevye, the heart of ‘Fiddler,’ was played by an excellent character actor, but one not right for this show. He lacked the heart, he wasn’t musical, and if he was a Jew, it was successfully hidden. This gimlet-eyed search for what is theatrically convincing leads Laurents, following a suggestion by Tom Hatcher, his companion of 52 years who died of lung cancer in 2006, to transform the new production of “West Side Story” into a bilingual show, with some songs and dialogue in Spanish (“I Feel Pretty” becomes “Siento Hermosa”). This is meant to counteract sour memories of the risible 1961 Hollywood version, which was hobbled by “peroxided, Max Factored Jets” and “pancaked Sharks in silk blousons and their Day Gloed, Carmen Mirandaed girls.”

Laurents thinks the cast of “West Side Story” should look and act like “young killers” and that the show’s theme is tragic, not cosmeticized: “Love cannot survive in a world of bigotry and violence.” This Hispanization makes sense; the most vibrant performance of Bernstein’s “Symphonic Dances From West Side Story” in years is by Venezuela’s Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra, led feverishly by Gustavo Dudamel.

Laurents’s ceaseless quest for dramatic reality is also reflected in a take-no-prisoners attitude offstage, which can leave colleagues aghast. In “Put on a Happy Face: A Broadway Memoir” (Union Square Press, 2008), Broadway composer Charles Strouse recounts how Laurents once answered the door to his apartment while “giggling uncontrollably” and then explained his high spirits gleefully: “Tony Perkins has AIDS!” While actor Anthony Perkins (1932–1992) had a closeted and arguably hypocritical bisexual life, Laurents’s schadenfreude in anecdotes of this kind reveal him to be lacking warmth or even a basic sense of pity.

Did Laurents’s courageous pioneering status as an advocate of realistic portrayal of Jewish and gay (the latter in the musical “La Cage aux Folles”) subjects require him to be, or become, a similarly ruthless version of Harry Bogen or Sammy Glick? In his previous book, “Original Story By: A Memoir of Broadway and Hollywood” (Knopf, 2000), Laurents angrily attacks director Sydney Pollack (1934–2008) for removing Jewish left-wing political content from Laurents’s screenplay for the 1973 Barbra Streisand film, “The Way We Were.” Will Laurents ever mellow?

In a 2003 interview in the journal American Drama, director Nicholas Martin (born Joel Levinson in Roosevelt, N.J.) said of Laurents: “He’s fierce; he’s personally fierce for better and for worse, and you feel in his plays the incredible power of his ferocity and now his endurance.” The motivation for the persistent Jewish content in some of Laurents’s more recent, neglected plays, like “My Good Name” (1996), “Jolson Sings Again” (1999), “Claudia Laszlo” (2001) and “Big Potato” (2000; reprinted in “Selected Plays of Arthur Laurents” [Watson-Guptill Publications, 2004]), are explained by the playwright himself in American Drama: “It comes down to what sets me raging — it’s injustice — the treatment of the Jews infuriates me.” Yet, even for this ferocious talent, rage alone may no longer provide sufficient inspiration. “Mainly on Directing” contains repeated references to the afterlife, where, according to Laurents, Hatcher is still reading his writings, watching his stagings and encouraging him.

On a Broadway where musicals are almost all prefabricated marketing ventures of the pestilential “Mamma Mia!” variety, we should be grateful to see a work of substance like “West Side Story” brought to new life, as the word “revival” should mean, but so rarely does. Ticket buyers to Broadway musicals have been suffering fools gladly for years, and Arthur Laurents is needed more than ever, to remind us that intelligence can indeed thrive in this sadly dumbed-down genre.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.

Below is a video podcast of Arthur Laurents, in conversation recently with journalist Charles Kaiser, at The Lesbian, Gay Bisexual and Transgender Community Center in New York City.

–

For more information about the new Broadway revival of “West Side Story,” see the show’s official Web site

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO