A Blazing Defense of Individualism

Self-Portrait With Flames: Carlo Michelstaedter stares out from the fire of his provocative philosophy. Image by Biblioteca Statale Isontina

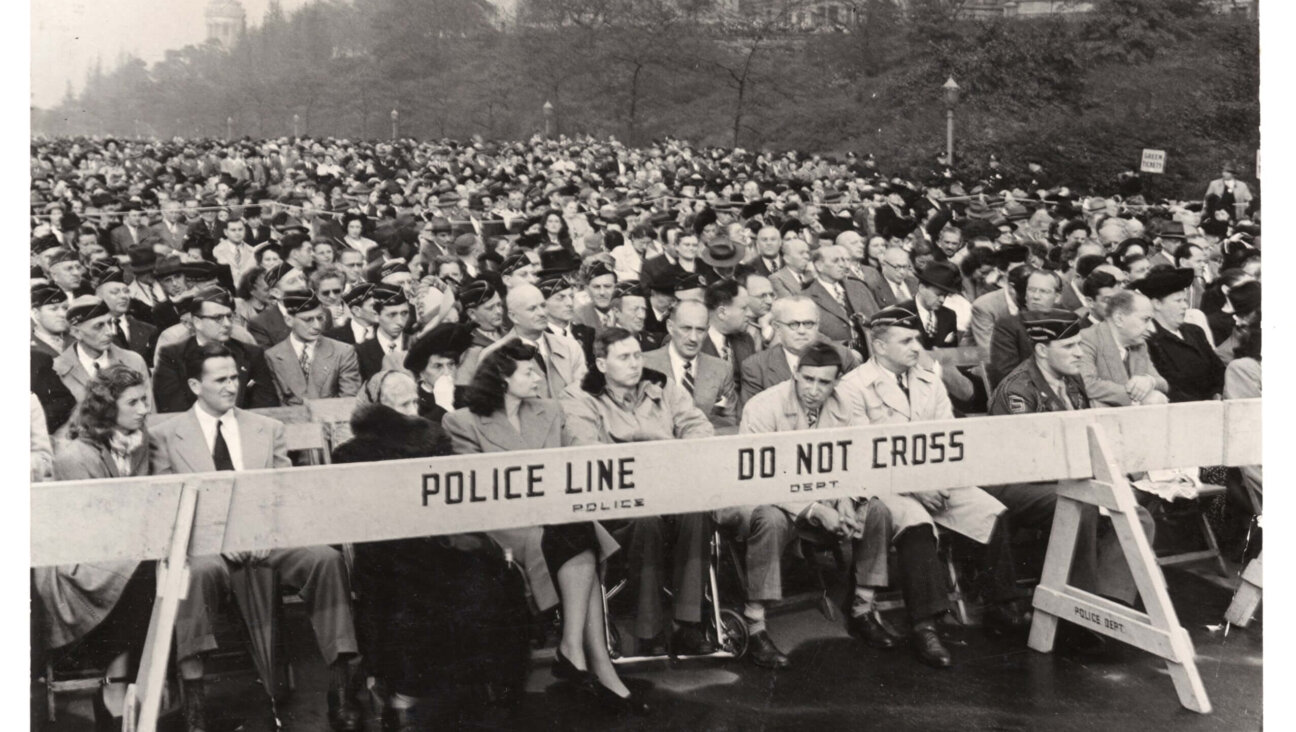

When the brilliant young Italian-Jewish philosopher, poet and artist Carlo Michelstaedter killed himself in 1910 at age 23, he must not have suspected that a century on, he and his works would be internationally celebrated. After initial neglect, a major exhibit, “Carlo Michelstaedter. Far Di Se Stesso Fiamma” (“Carlo Michelstaedter: Transform Yourself Into a Flame”), opened in October and is on view until February 27 at the National Savings Bank Foundation (Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio) of his native city of Gorizia in northeastern Italy, close to the Slovenian border.

Self-Portrait With Flames: Carlo Michelstaedter stares out from the fire of his provocative philosophy. Image by Biblioteca Statale Isontina

“Carlo Michelstaedter. Far Di Se Stesso Fiamma,” features more than 250 manuscripts, books, photos and artworks. Of the last-mentioned, the most impressive are several poignantly painted self-portraits that would express melancholy even if the author’s tragic fate were not known. Accompanied by an elegant, profusely illustrated catalog from Marsilio Editori, the exhibit gives a strong sense of the complex identity issues confronted by sensitive, intellectually creative Italian Jews at the turn of the century. As Thomas J. Harrison’s insightful “1910: The Emancipation of Dissonance” (University of California Press, 1996) observes, the Michelstaedter family was “firmly Italian, even if educated, like most citizens of the [Austro-Hungarian] empire, primarily in German. Italian for themselves and Austrian for the state, they were primarily Jews for others. On such disinherited fringes of states, questions of identity are not a choice but a painful fatality.”

Michelstaedter was not alone; fellow northern Italians such as the tormented novelist Italo Svevo (born Aron Ettore Schmitz) and poet Umberto Saba (born Poli) were other neurotic overachievers. Yet their achievement came at an obvious cost.

“Carlo Michelstaedter. Far Di Se Stessso Fiamma” reminds us of the intense life drama that is in good measure the reason for the ever-increasing interest in Michelstaedter’s life and in his philosophy.

The exhibition marks a revived Italian interest in the various aspects of Michelstaedter’s work and life. A new Italian play, “Michelstaedter: Biografia di un Pensiero Furioso,” (“Michelstaedter: Biography of a Blazing Thought”), (co-written by filmmaker Marco Colli and the Budapest-born Italian-Jewish novelist Giorgio Pressburger, toured through Croatia and Slovakia in November and December 2010. And a flurry of new books about Michelstaedter has appeared from such leading Italian publishers as Adelphi Edizioni; Mimesis Edizioni and Donzelli Editore.

English-speaking readers, too, may celebrate Michelstaedter through two available annotated translations of “Persuasion and Rhetoric” (“La Persuasione e la Retorica”), the thesis that he completed just before his death. Published by Yale University Press in 2004 and in an alternative translation from The University of KwaZulu-Natal Press in 2007, “Persuasion and Rhetoric” is a somber, unforgivingly harsh yet inspiring plea for individuality in a society of mass production. Repeatedly quoting Ecclesiastes, among many other authorities, Michelstaedter puts forward his argument that by shunning what he calls “rhetoric,” or the million ways in which people deceive themselves in order to find life acceptable, we may arrive at “persuasion,” or the state of self-determining individualism, living in the moment as if each second were to be our last.

For example, “Persuasion and Rhetoric” offers observations on charity, or what Michelstaedter terms the “duty… to give everything and demand nothing.” Calculated charity, or what Michelstaedter calls “giving for the sake of having given,” is not genuine generosity, but rather a form of “demanding” in the young philosopher’s eyes insofar as the act of giving is predicated on receiving something in return, an elevated status in one’s own eyes or in the eyes of the world in general.

Comparably flawed, Michelstaedter charges, is the concept of people feeling comfortable because they are insured (a telling viewpoint, since Michelstaedter’s father, Alberto, was a prosperous insurance company executive). The chapter “Rhetoric of Life” in “Persuasion and Rhetoric” contains an ironic dialogue in which a “portly gentleman” brags that he is insured against theft, fire and automobile accidents, to which his interlocutor comments: “But then death. We all die!” The gentleman returns with: “Not at all. I’m insured in case of death.”

Michelstaedter was preternaturally aware of the transitory precariousness of the culture in which he lived, noting that as technology advanced, craftsmanship was eliminated: “One hardly finds anyone who knows how to shoe a horse anymore; and the master stonecutters, and carpenters, and weavers, etc. Their places have been taken by the masses of sad, dull factory laborers who know but one gesture.”

Franz Kafka, another great master of expressing the precariousness of modern life, was himself an insurance company employee. And Michelstaedter shared with Kafka, Arthur Schnitzler and Svevo the vulnerability of being a minority in multiple ways — living in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, yet never entirely belonging. As Michelstaedter wrote in an untitled, posthumously published poem, his attitude toward “la patria,” his homeland, was complex, yet typically inspirational and energetic.

Homeland is not

cozy bedding

for cosseting and tedium and exhaustion;

but within the breast, imperiled,

whoever mentions it

must create it.

Non è la patria

il comodo giaciglio

per la cura e la noia e la stanchezza;

ma nel suo petto, ma pel suo periglio

chi ne voglia parlar

deve crearla.

Drawing strength from such starkly creative absolutists as Beethoven, Ibsen, Giacomo Leopardi and Tolstoy, Michelstaedter, in his preface to “Persuasion and Rhetoric,” modestly warns the reader that his book was written “in a manner to amuse no one — without philosophical dignity or artistic concreteness, but rather as a poor pedestrian measuring the terrain with his steps.” Yet far from being a mere flâneur (or intellectual stroller, as celebrated by the German-Jewish essayist Walter Benjamin in his “Arcades Project”, Michelstaedter turns out to be a prophet in many ways. Surprisingly, he even anticipates Werner Heisenberg’s 1927 Uncertainty Principle by commenting that “because scientists cannot discard their skin with impunity like silkworms in order to watch how things are made, we must admit that objectivity is… ‘in some manner’ a subjectivity.” In short, by the very act of observing, the scientific observer is inserted into nature and inevitably alters whatever is being observed.

Such acute awareness is more than just prescient; it becomes an expression of inner virtue, and the kind of creativity that Michelstaedter himself urged on anyone contemplating the term “homeland” as cited previously. In yet another anniversary-year homage, Canadian author Jacques Beaudry has published an imaginative book-length essay, “Le Tombeau de Carlo Michelstaedter,” “Carlo Michelstaedter’s Sepulcher,” with Les Éditions Liber, a small Montreal press. Beaudry cites a quote by Siegfried Kracauer to argue that Michelstaedter was a “Lamed-Vavnik,” or one of the 36 hidden Tsadikim, upon whom the world depends for its continued existence, according to Jewish lore. Michelstaedter’s death by suicide, according to Beaudry, was merely a means of avoiding the need to “dilute his existence” by the compromises that a full lifespan almost inevitably necessitates.

In “1910: The Emancipation of Dissonance,” Harrison notes that Michelstaedter’s suicide also spared him from the fate of his mother and sister, who were murdered at Auschwitz in 1943. Although his life was short, Michelstaedter managed to produce a book that continues to inspire readers today with its exhortations, such as: “You must create the world, create each thing: in order to possess your life as your own.” This idealistic advice transforms what otherwise might be a morbid cult surrounding a suicidal writer into something entirely more constructive.

Through no fault of his own, Michelstaedter had reason to consider suicide as a recurrent event in his life. When he was 8 years old, in 1885, his cousin, Ada Coen Luzzatto, poisoned herself. In 1907, Michelstaedter’s ex-girlfriend, Nadia Baraden, committed suicide, as did his elder brother, Gino, in 1909. Even so, suicide does not define or limit Michelstaedter. Instead, readers continue to marvel at his iconoclastic thoughts, which have made him into an unlikely icon, the subject of a bronze statue unveiled in Gorizia last November.

The somewhat idealized new statue is a far cry from Michelstaedter’s own uneasy self-portraits, which, like his writings, scrutinize truth “in a manner to amuse no one,” and thereby produce insight instead of diversion, defiantly setting aside charm or winsomeness as mere “rhetoric.” “Persuasion and Rhetoric” may not be an entertaining volume, but it is still indispensable for readers today.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.

“Carlo Michelstaedter. Far Di Se Stesso Fiamma” is on display at the National Savings Bank Foundation in Gorizia through February 27.

Watch a short documentary homage to Carlo Michelstaedter filmed in his native city of Gorizia, Italy.

Watch a video following a tour guide in Gorizia to the main places of Michelstaedter’s life.

Watch an Italian TV report on the centenary museum exhibit in Gorizia.

And watch Professor Piero Pieri of the University of Bologna lecturing in April 2010 at the Italian Jewish Book Festival in Ferrara on Michelstaedter’s Jewish influences.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

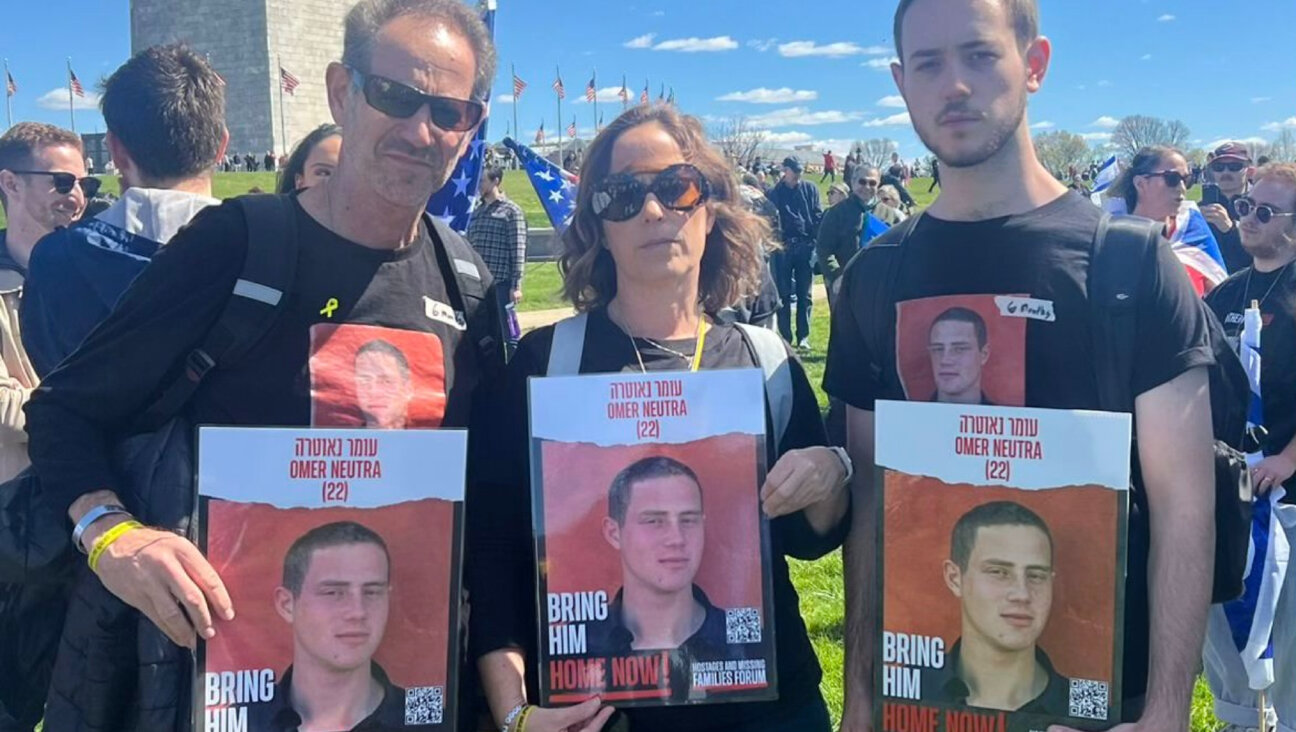

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!