A Museum as Big as Texas

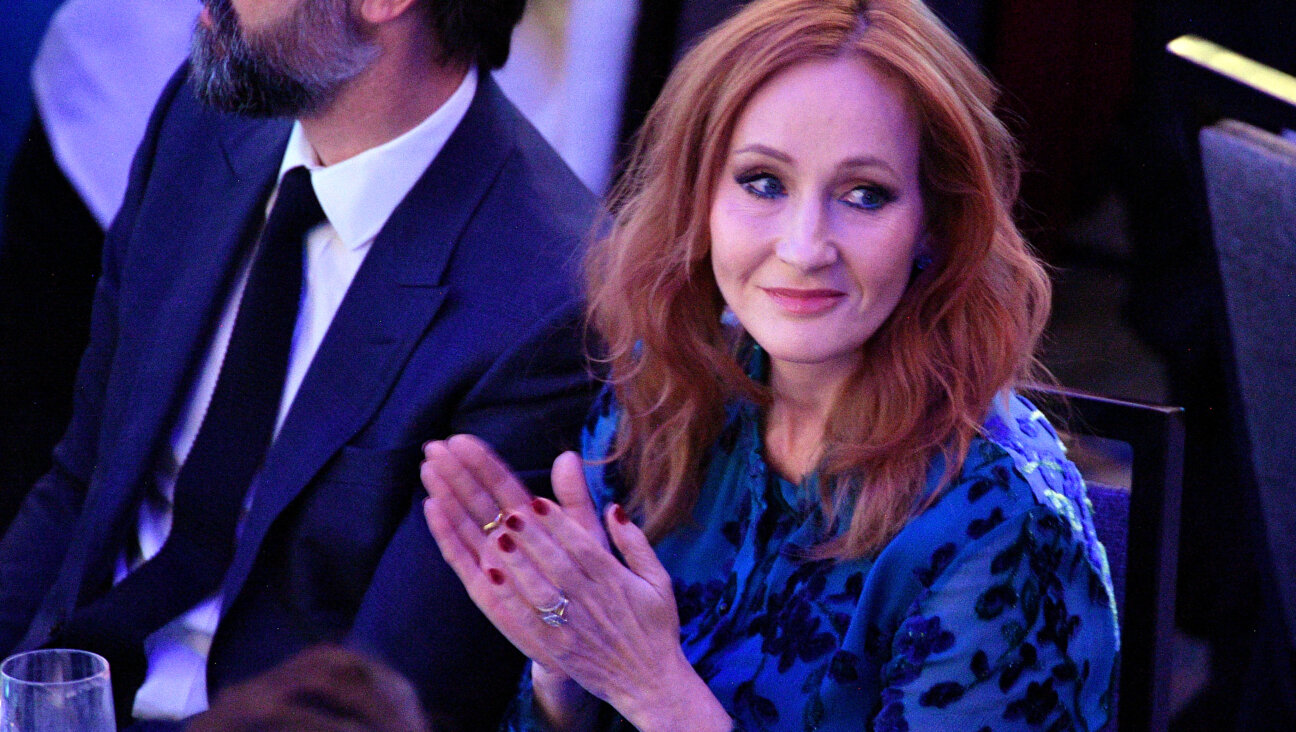

Big Deal: The Dallas Museum of Biblical Art boasts 30,000 square feet of exhibition space. Image by Courtesy of scott peck

All That Glitters: The National Center for Jewish Art is housed within Dallas’s Museum of Biblical Art. Image by menachem wecker

Perhaps surprisingly, the newly launched National Center for Jewish Art doesn’t reside on the East Coast, in California, or in Chicago. Instead, it is housed at Dallas’s Museum of Biblical Art, which lives up to its state’s reputation for enormity. Even excluding Gib Singleton’s soon-to-be-installed, huge outdoor “Via Dolorosa” installation, the museum boasts 30,000 square feet of exhibition space — more than triple the combined area of Manhattan’s Museum of Biblical Art and St. Louis University’s Museum of Contemporary Religious Art.

“No one is really doing what we are doing on the scale of what we are doing,” says Scott Peck, the Dallas museum’s director and curator who studied for two years in a Jewish ceremonial art certificate program at Jewish Theological Seminary.

Last October, Peck expanded the museum’s Judaica collection and launched the National Center for Jewish Art. The opening, and its inaugural exhibit, featured some 60 works by Houston artist Barbara Hines.

“We will continue to be more aggressive with having a dedicated space for the research, study and exhibition of Jewish and Israeli art,” Peck said in a recent interview.

The museum’s collection of 2,500 works includes what the museum describes as “a Veronese drawing from the studio of Benjamin West and a painting from the School of Botticelli,” paintings by John Singer Sargent and Andy Warhol, and a life-sized, Vatican-authorized bronze replica of Michelangelo’s “Pietà.” Its Jewish holdings feature such artists as Marc Chagall, Leonard Baskin, William Gropper, Jack Levine, Jacques Lipchitz, Ben Shahn and Max Weber, as well as ceremonial art.

When he installed Dallas Jewish artist George Tobolowsky’s work in November 2012, Peck hadn’t anticipated that Tobolowsky’s menorahs, made of polished steel found objects including drills and airplane and truck parts, would still be on view two years later. But he now anticipates that the work, which is very popular with husbands and boyfriends whom he says often get dragged to the museum, will remain on view for “quite a while.”

“They have a pretty industrial feel to them. For men, they tend to really connect with this artwork,” he says.

But women, too, are drawn to the power tool menorahs. “I’ve seen a bunch of creative menorahs used by Chabads around the country, but nothing quite like this,” says Susanne Goldstone Rosenhouse, the National Jewish Outreach Program’s social media coordinator in Dallas, who visited the museum in October 2013. “We were blown away by the creativity and physical work that went into creating these pieces of art.”

The museum’s collection of more than 100 Bibles, including some dating back to the 15th century, were also standouts to Rosenhouse.

Zsuzsanna Ozsváth, a Holocaust studies chair at the University of Texas at Dallas, said that the museum’s collection “is remarkably interesting and significant,” and added that several of the Holocaust paintings were “truly moving and important.”

The museum also earned accolades from the Texas Jewish Arts Association. “They have been more than welcoming to us and to the Jewish Community,” says TJAA president Veronique Jonas. Nancy Cohen Israel, a board member at the association (where the power tools menorah artist Tobolowsky is also on the board), agrees. “We feel fortunate to have a place in Dallas that exhibits the work of our local Jewish art community,” she says.

Big Deal: The Dallas Museum of Biblical Art boasts 30,000 square feet of exhibition space. Image by Courtesy of scott peck

But some in the Dallas Jewish community are unhappy that a museum “with clearly Christian roots and intent has captured the attention and favor of some Jewish artists,” says Debra Polsky, executive director of the Dallas Jewish Historical Society.

Polsky says that the museum sometimes holds prayer services before its events, but that it does not include non-denominational prayers. This reluctance, she says, “left a bad taste in some people’s mouths.” Dallas’s Jewish community is “skittish” about proselytizers due to the work of several messianic congregations, she says.

Even if prayers and proselytizing were once an issue, things have changed, according to Cohen and Jonas. The belief that the museum exclusively caters to Christians is a minority view that originated “quite a few years back” and probably comes from people who have little knowledge of the museum, according to Jonas. The new Jewish art center “should assuage all such fears,” she says.

Cohen notes the museum’s detractors, as well as its by-laws “espousing fundamentalist Christian ideas.” But she doubts that the prominent Jewish artists, gallerists, and scholars who make up the new center’s board would be involved if it was too evangelical.

Peck, who identifies with both Judaism and Christianity and who last summer researched relatives murdered in the Holocaust at Yad Vashem, is also aware of criticism. “The museum is not a religious institution,” Peck says. “We are an art museum.”

Education about the museum, says Peck, who holds a museum studies master’s degree from University of Texas at Dallas, is “a constant thing.” Some Jews think the museum is Christian; some Christians consider it Jewish; Catholics have found it Protestant, and vice versa; and it has struck some Mormons as anti-Mormon.

“This is one of the many challenges in having an art museum that deals with art having a biblical theme that is in the middle of the Bible belt.”

Menachem Wecker is the co-author, with Brandon Withrow, of the recent book “Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher Education,” published by Cascade Books.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

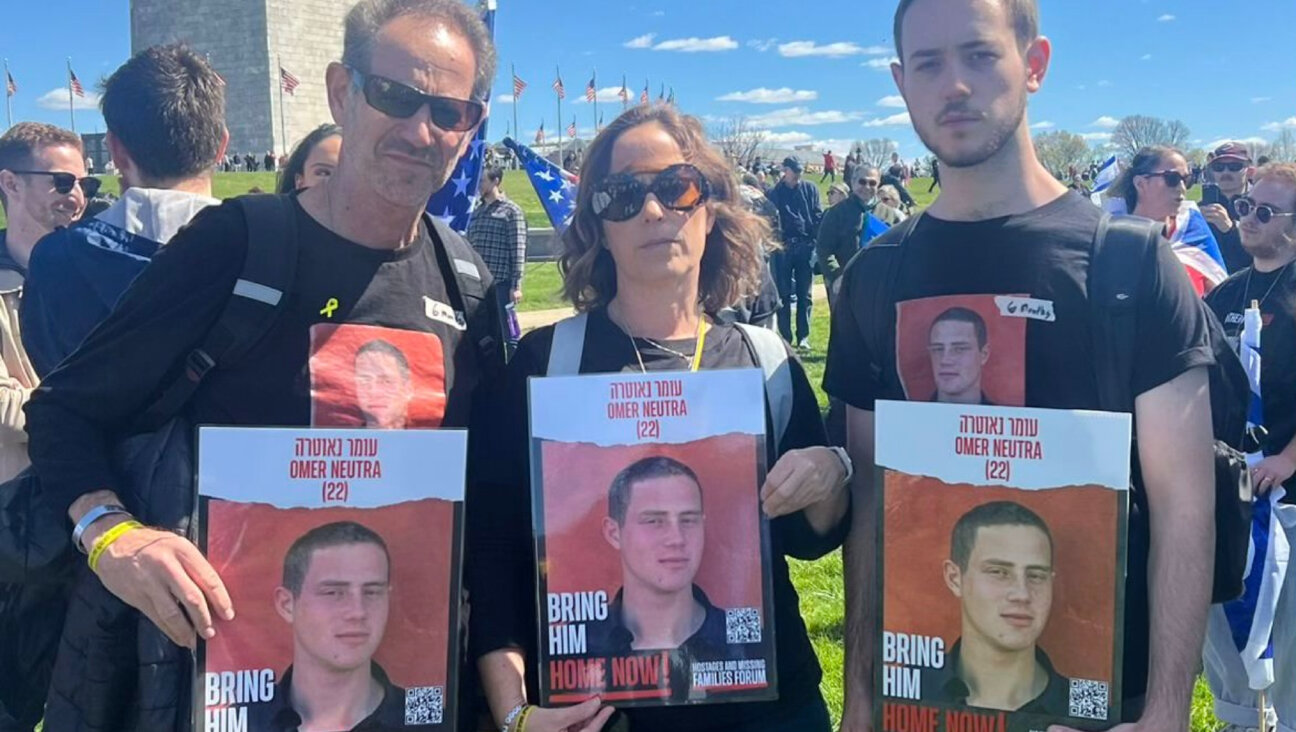

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!