The Paradox Of Jared Kushner, A ‘Man Without Qualities’

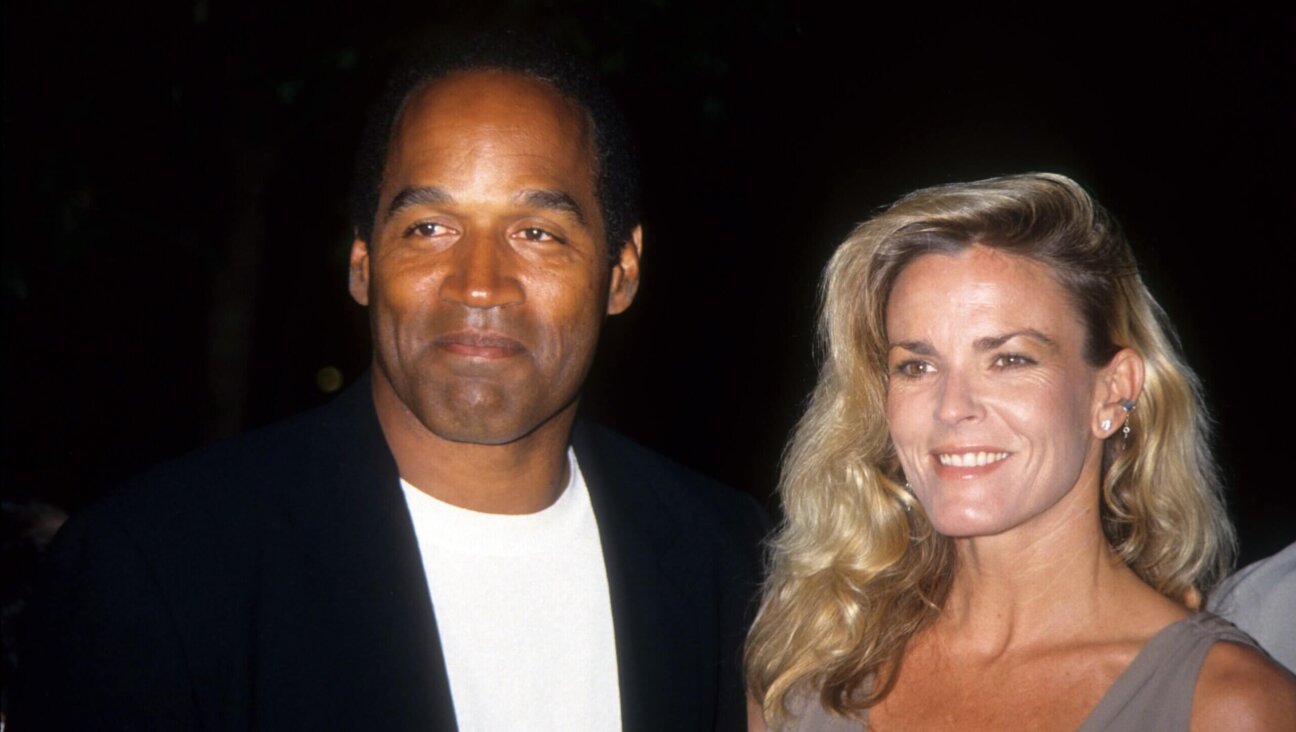

Image by Getty Images

Seventy-five years ago, Robert Musil died in Switzerland. The Austrian writer had taken refuge there in 1938 with his Jewish wife Martha, and as the war progressed, he spent his time trying to make ends meet and to complete his novel, “The Man Without Qualities.” Neither effort was successful: Musil’s life ended in poverty when a stroke felled him in 1942, while his novel, clocking in at 1,000 pages, was still unfinished.

Despite, or perhaps partly because of its lack of ending, “The Man Without Qualities” has become a modernist classic. But recent events in the United States have made this timeless classic once again timely.

It is set in the fictional country of Kakania — a scarcely fictionalized Austro-Hungarian Empire. Like the United States today, Kakania is being pulled in opposing directions by the forces of authoritarianism and liberalism. And like the United States today, Kakania is a world, Musil writes, where “persons who would before never have been taken seriously became famous.” A place where once-sharp boundaries have blurred, and where once-meaningful values have vanished, Kakania steeps in narcissism and greed. Sound familiar?

But perhaps most relevant is the novel’s main character, Ulrich, who weaves his way aimlessly across the novel’s pages. Unburdened by a last name, Ulrich is also unburdened by character traits (he is the eponymous man without qualities). This absence of any recognizable quality he can call his own is, well, Ulrich’s defining quality.

Ulrich’s lack of personality is a lacuna that helps explain the novel’s lack of a plot. It’s hard, after all, to drive a story without someone behind the narrative wheel. But it also helps to explain one of the great mysteries of our current regime: the plotless nature of one of its leading figures, Jared Kushner.

Since last year’s presidential election, Kushner has achieved a remarkable feat: He is both everywhere and nowhere, omnipresent and wholly absent. In general, we know where Kushner is: ensconced in the West Wing of the White House. Like a waxen Waldo, his face hovers over his father-in-law’s shoulder in countless photos.

Yet we have no idea what he is: His voice is unheard, his principles are unknown and, as far as observers can tell, his influence is unfelt. And yet, there he is, always in the public eye, always in our thoughts — the puzzling presence of a man whose greatest quality is his moral absence.

Who is this man who seems so ardently to exist as such and yet fails to exist in any particular, meaningful way? He is another man without qualities, and Musil’s anti-hero serves as a perfect guide.

For Jared is like Ulrich in more ways than one. Ulrich is a 30-something who, thanks to his father’s worldly success, has no material or financial concerns. He is set for life, yet life eludes his grasp as he listlessly pursues one vocation after another. One fine day, though, he finds himself named — thanks to his father’s influence — as honorary secretary of the “Parallel Campaign,” the series of festivities to celebrate the 70th jubilee of Emperor Franz Josef.

Inevitably, the Parallel Campaign provides Ulrich no more meaning or purpose than did his earlier activities. He seems unbothered, though, by this state of affairs; after all, he is a man “who never needed that overhauling and lubrication that is called probing one’s conscience,” Musil writes. Why would he? With neither fixed qualities nor character-based values, Ulrich hasn’t a shred of “own-ness.” Instead of defining events according to core principles that might define what he is — he allows events to define him. When an acquaintance dubs Ulrich as a “man without qualities,” he explains that it means “nothing.” Making certain there is no confusion on this score, the acquaintance expands: “It is precisely nothing!”

Yet Ulrich has one saving grace: He is awoken to his tragic condition. His self-awareness extends to his awareness that he doesn’t have a self, in a perfect little paradox that is also his moral alibi. And herein lies the difference between Ulrich and Jared.

Kushner has yet to be graced with this awareness. As ill-suited for global and domestic policy-making as he was for a Kevlar vest during his lightning visit to Iraq, Kushner embodies Musil’s observation that being Socratic means feigning ignorance, while to be modern means to actually be ignorant.

Thus, the former real estate developer is unfazed by the Kakanian absurdity of overseeing a steadily compounding number of duties, from bringing peace to the Middle East to bringing answers to our opioid crisis, none of which he is faintly qualified for. As one insider remarked in a much-discussed Vanity Fair profile, what is so off-putting about Ivanka Trump as well as Jared Kushner is “that they do not grasp their essential irrelevance. They think they are special.”

In the same article, a former associate captured that elusive yet essential Musilian quality to Kushner’s nature. While Ivanka Trump, the source remarked, was the “one with the personality,” Jared was usually “pretty quiet.” In fact, the former acquaintance continued, “there was a certain formless quality to Jared.”

Ulrich tried to take the measure of his own formlessness – without success. But in the end, Musil’s anti-hero became an activist, at least when he wasn’t a nihilist. Should the day ever arrive when Jared Kushner undertakes a similar effort, he will discover that while nihilism amounts to little when yoked to the Parallel Campaign, it is a very different matter when allied to a father-in-law’s presidential campaign.

Robert Zaretsky is a professor of history at the University of Houston, and the author, most recently, of “Boswell’s Enlightenment.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!