Nazi collaborator monuments in Australia

Honors for collaborators from Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Serbia and Ukraine

Left: SS Galichina recruitment march, Kolomyia, 1943. Right: neo-Nazi march on the 73rd anniversary of SS Galichina’s founding, L’viv, April 28, 2016 (Yuriy Dyachyshyn/AFP via Getty Images). Image by Forward collage

This list is part of an ongoing investigative project the Forward first published in January 2021 documenting hundreds of monuments around the world to people involved in the Holocaust. We are continuing to update each country’s list; if you know of any not included here, or of statues that have been removed or streets renamed, please email [email protected], subject line: Nazi monument project.

Monuments to Croatian collaborators

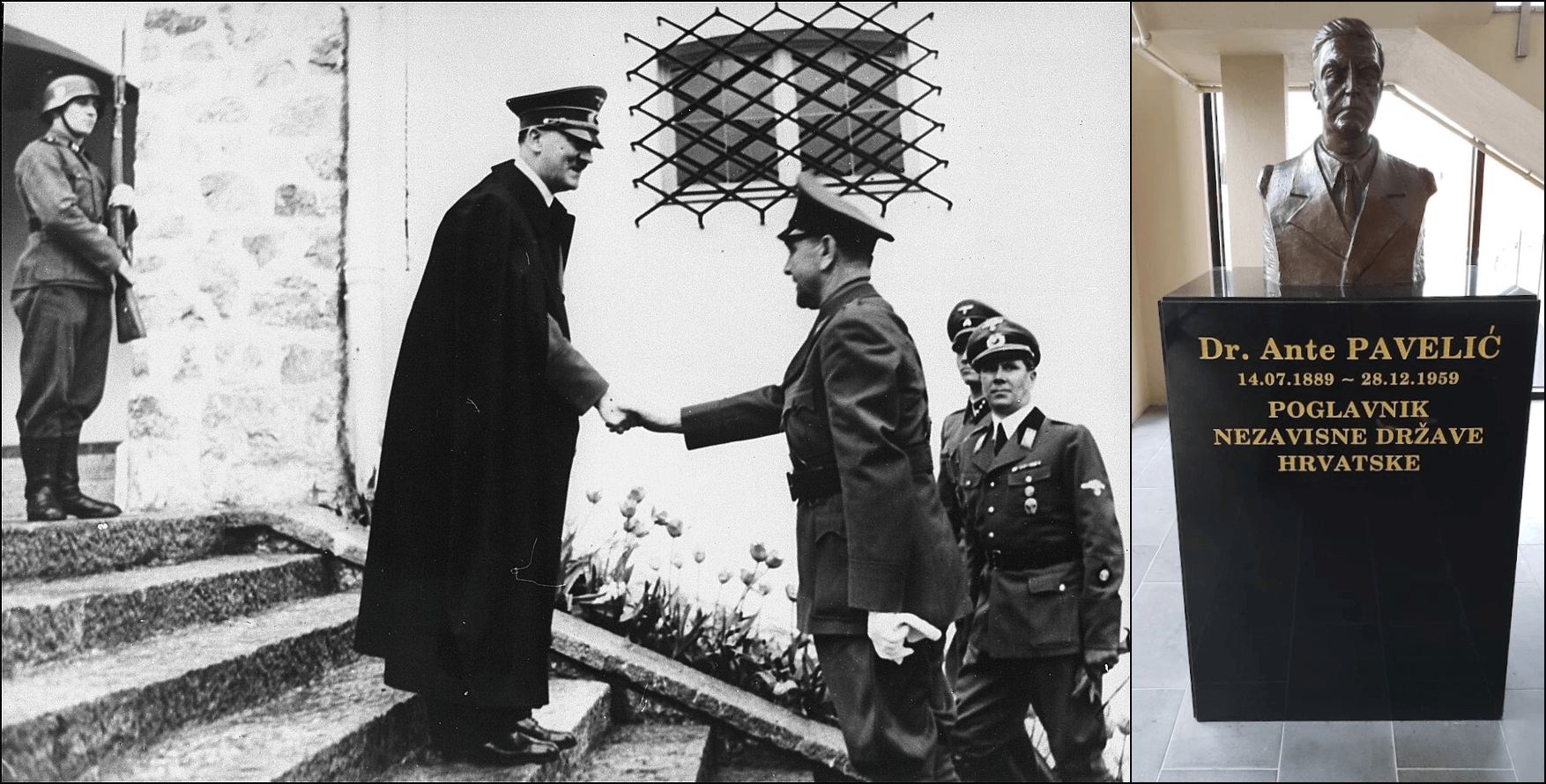

Melbourne — A bust of Hitler ally Ante Pavelić (1889–1959) in Melbourne’s Croatian House.

Pavelić was the leader of the fascist Ustasha regime, which systematically murdered tens of thousands of Jews, Serbs, and Roma, the most infamous killings taking place at the Jasenovac concentration camp.

Above left, Pavelić meets with Hitler June 9, 1941. For a fascinating article on how Croatian fascist supporters came to be in Australia, see Balkan Insight. Below, Ustasha guards confiscate belongings from prisoners entering Jasenovac.

For Ustasha monuments in other countries, see the Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina sections.

Monuments to Latvian collaborators (section added June 2025).

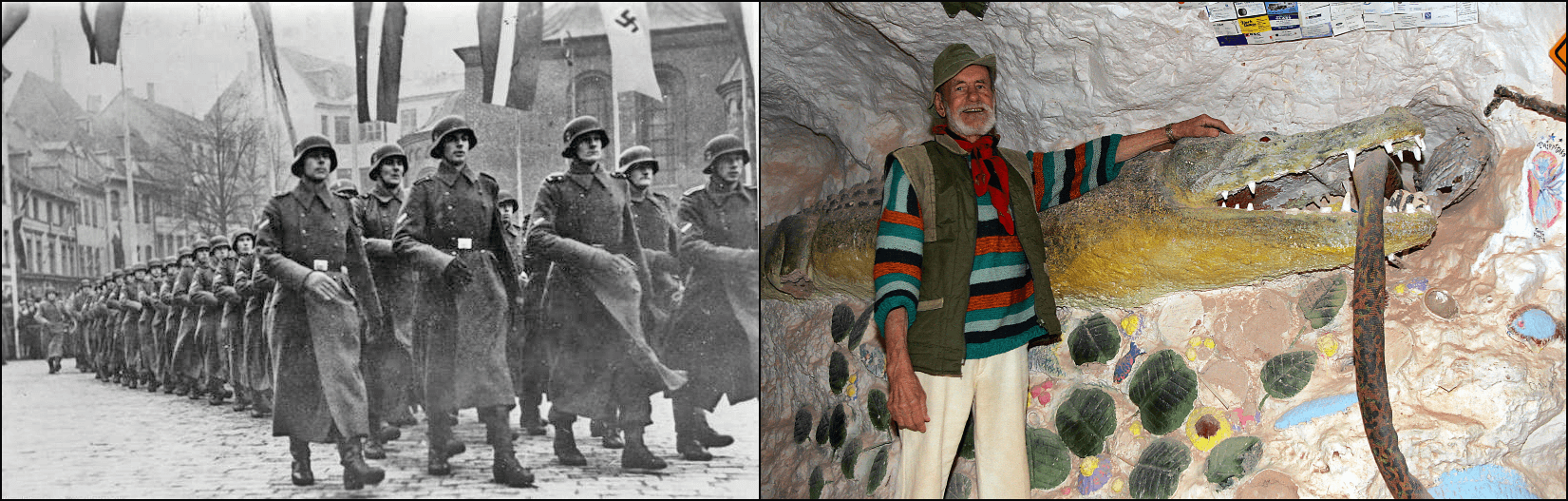

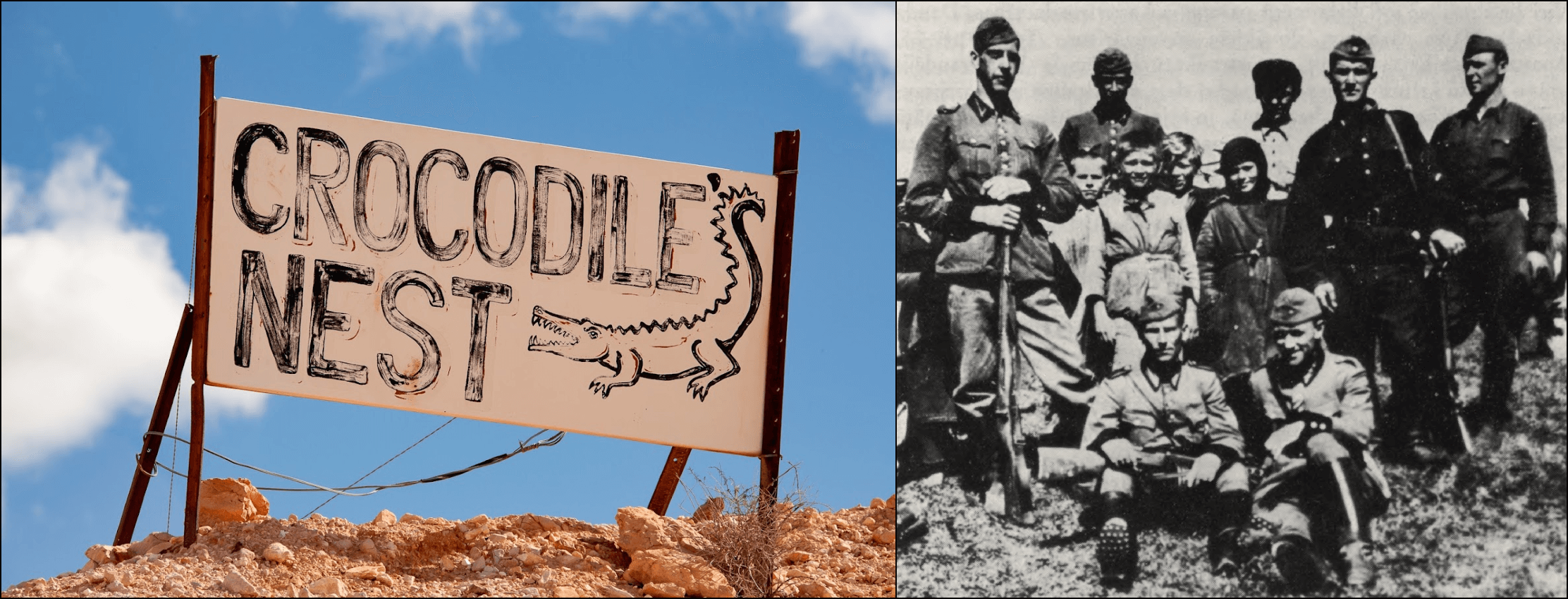

Coober Pedy – This strange tourist spot is known for opal mines as well as its underground infrastructure, including subterranean hotels and churches. A major attraction is “Crocodile Harry’s Underground Nest,” the home of Arvīds Blūmentāls aka “Crocodile Harry” (1925–2006), a Latvian immigrant and infamous crocodile hunter, above right.

During WWII, Blūmentāls served Nazi Germany in the 25th Schutzmannschaft Battalion, an auxiliary police unit under control of the Ordnunsgpolizei and the SS – the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. Schutzmannschaft battalions played a crucial role in suppressing anti-Nazi resistance; they were also involved in perpetrating the Holocaust (three-quarters of Latvia’s Jews were slaughtered). Afterward, Blūmentāls fought in the Latvian Legion, a unit in the Waffen-SS, the military component of the SS.

The Legion was comprised of the 15th Waffen Grenadier (1st Latvian) and the 19th Waffen Grenadier (2nd Latvian) divisions of the SS. Today, Latvia holds annual marches celebrating the Latvian Legionnaires; these have been condemned by Jewish organizations.

After the war, Blūmentāls escaped to Australia and began a new life as the notorious “Crocodile Harry.” He settled in Coober Pedy in 1975, constructing a bizarre underground dwelling filled with tributes to his fame and virility, above right. It draws tourists to this day.

Typical reviews of this shrine to Blūmentāls say nothing about him being a Nazi collaborator who fought in two Third Reich military units.

Above left, Latvian SS soldiers parade through Riga. Below left, a welcome sign to Crocodile Harry’s Underground Nest; below right, fighters from the 25th Schutzmannschaft Battalion pose with children, 1943. See coverage in the Awl as well as the Latvia and Belgium sections for more monuments to Latvian collaborators, including Blūmentāls.

Monuments to Lithuanian collaborators (section added April 2022)

Update (June 2022): After an investigation in collaboration with the Sydney Jewish Museum, the art gallery was renamed and the plaque removed. See statements from the Wollongong city council and coverage in the Guardian and the Australian Jewish News.

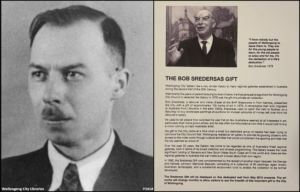

Wollongong, New South Wales – In March 2022, this coastal city was rocked by an extensive Guardian article exposing a beloved local hero as a Lithuanian Nazi collaborator. Bronius “Bob” Sredersas (1910–1982) was a quiet man who had immigrated to Australia from Lithuania after living as a displaced person in Europe; over the years, Sredersas had amassed an impressive art collection, which he donated to the city in 1976. The collection allowed Wollongong to establish the public-owned Wollongong Art Gallery, a spectacular cornerstone of the city’s art scene.

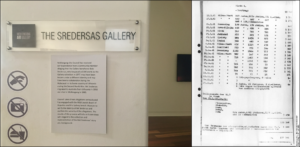

The donation, combined with the story of the unassuming immigrant steelworker who saved his paychecks to quietly collect art, was a sensation. Sredersas was lauded by the city and is celebrated in the gallery, where he has a plaque (above right) as well as a separate exhibit hall named after him.

Sredersas’ dark past was unearthed due to years of painstaking research by Michael Samaras, a former Wollongong councilman. In his quest, which was aided by the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Jerusalem branch director and Nazi hunter Efraim Zuroff, Samaras discovered Sredersas had served in the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the intelligence service of the Nazi Party.

The SD played a crucial role in the Holocaust, especially the Holocaust by bullets in Eastern Europe. It provided men for the Einsatzgruppen death squads which, together with local collaborators, were responsible for massacring 95–96% of Lithuania’s Jews. Whether Sredersas participated in the Holocaust or other war crimes is unknown; what’s clear is that he served in a key organization which enabled the Third Reich to perpetuate the Holocaust and subjugate conquered lands.

There is no indication that Wollongong’s city council, or the gallery, knew of Sredersas past until Samaras approached them in January 2022. The Guardian reported that the council initially told Samaras it did not plan to “take any further steps in this matter,” but after the March article appeared, the city changed committed to work with Jewish organizations and museums to investigate the situation.

In the meantime, the museum placed a notice in the Sredersas gallery explaining this to the public (below left). Below right, a page from the infamous Jäger Report, a chilling account of the extermination of Jews in Lithuania and elsewhere by Einsatzkommando 3 of Einsatzgruppe A, a Nazi death squad partially composed of SD operatives.

Thanks to Matthew Buckley, a reader, who brought this story to our attention; Samaras for providing information on Sredersas, and Nicholas McLaren for the plaque photo. See podcast and follow-up coverage by The Guardian and the Australian Broadcasting Company (ABC), a public media outlet. For more honors to Lithuanian collaborators see the Lithuania and U.S. sections.

Monuments to Serbian collaborators

Canberra and Blacktown — A statue of Dragoljub “Draža” Mihailović (1893–1946) in front of a Canberra center named in his honor.

Mihailović’s Chetniks, a Serbian nationalist and Yugoslavian royalist militia, had collaborated with the Nazis and the Nazi puppet government in Serbia. At another point during the war, Mihailović cooperated with the Allies, using his troops to help rescue over 400 American airmen shot down in enemy territory. (Many thanks to Milijana Pavlović for aid in locating Chetnik statues outside Serbia.)

Below is another statue to Mihailović in Blacktown.

For more Chetnik monuments, see the Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, U.K., U.S. and Canada sections.

Monuments to Ukrainian collaborators

Wayville, South Australia — This memorial for soldiers who died for Ukraine features the lion and crowns insignia of the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS, also known as SS Galichina. This was a unit in the Waffen-SS, the military wing of the Nazi party, led by Heinrich Himmler, one of the principal architects of the Holocaust. Among the war crimes committed by this unit is the Huta Pieniacka massacre of Polish civilians.

Above left, an SS Galichina recruitment poster with the lion and crowns insignia. It features a quote from Mein Kampf: “Whoever wants to live must fight, and whoever doesn’t want to fight in this world of permanent struggle — he doesn’t deserve the right to live. Adolf Hitler.” Underneath is “SS Galichina is going to battle!”

Today, the use of SS Galichina insignia has become widespread enough to be included as a hate sign identifier for European soccer.

Below left, what is most likely an SS Galichina recruitment march, Kolomyia, 1943. Below right, torchlight march in honor of the 73rd anniversary of SS Galichina’s founding, L’viv April 28, 2016. The commemoration two years later involved hundreds giving coordinated Nazi salutes. See JTA report.

For Ukrainian monuments outside of Australia, see the Ukraine, Argentina, Austria, Germany, Italy, U.K., U.S. and Canada sections, particularly Canada, which saw a 2020 scandal centered around an SS Galichina memorial nearly identical to Wayville’s.