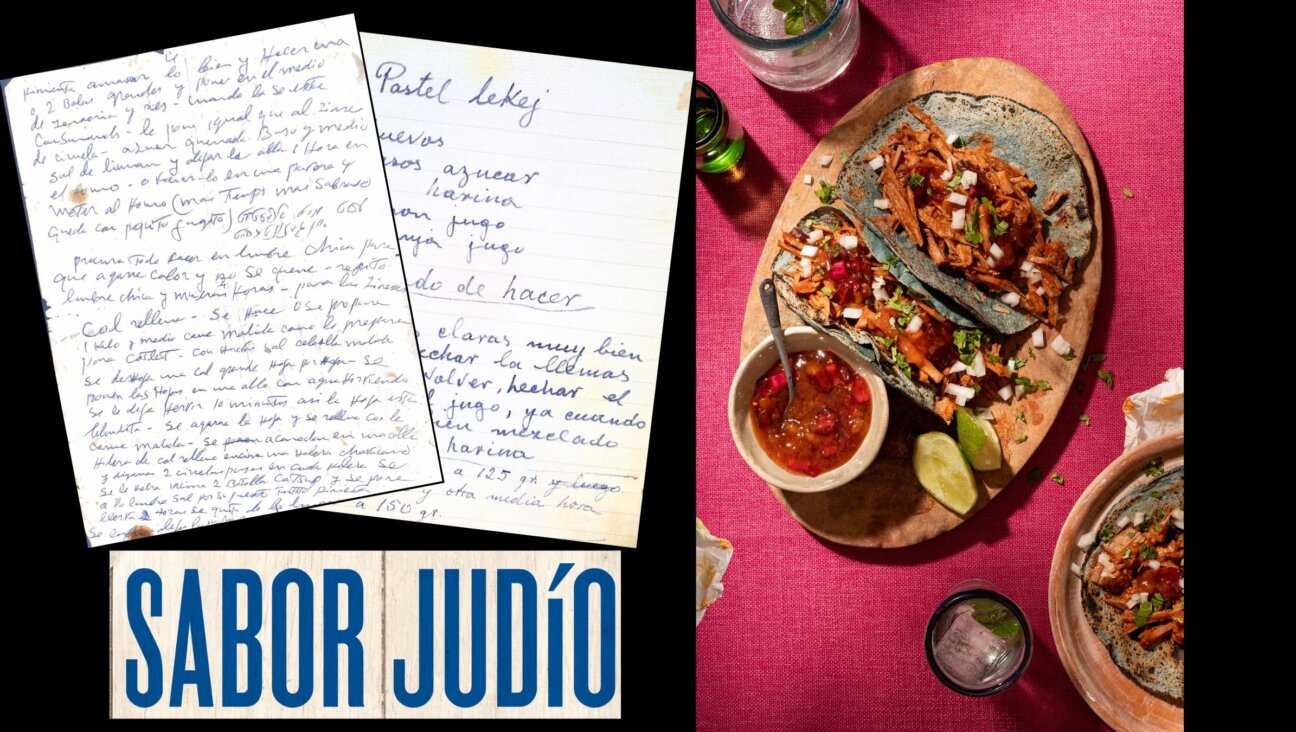

Kosher Pizza Goes Avant-Garde

Image by Facebook/Basil NY

It’s been a tough year for Basil, the upscale pizzeria turned Mediterranean restaurant that credits itself with bringing Kosher fine dining to trendy Crown Heights. First they sued a competing pizza restaurant, Calabria, for violating the halachic law of “hasagat givul,” which literally means boundary infringement and refers to unfair business competition that seeks to harm. Then they were stripped of their kashrut certification in what Basil called “a big misunderstanding.” Now they’ve been reborn as a Mediterranean restaurant. Are they kowtowing to Calabria, allowing Calabria to retain the stranglehold it has on the niche world of Crown Heights Kosher pizza? Is the reopening also a rebranding, now that vocal manager Clara Perez has left her post? Does the Jewish world really need another kosher Mediterranean joint? In the kill or be killed world of New York restauranteurs, can the food triumph?

In search of answers, I brave a violent winter storm and head to Basil to check out what the future of kosher dining has to offer.

In the past at Basil, waiting two hours for a table was not uncommon. On Basil’s website, in all caps, it is written: we do not take reservations! This time, I am ushered in.

The decor is cozy-suave, with exposed red brick walls, wooden no-nonsense black benches, square marble tables and a beehive-esque wall with stacked wine bottles inside a glass wall box.

At Basil, on the night of the new menu unveiling, the lights were dimmed and the mood was energetic. Dates. Pomegranate. Za’atar. Sumac. Lots of goat cheese. These are some of the staples of the reinvented menu, and with it have come some award-winning international chefs. Chef Avi Steinitz and Chef Eran Harel have relocated to Basil for a short-term residency to revive the menu and give it some Mediterranean flavor, while presumably lending their star power to the already famous (or infamous, depending on who you ask) institution.

I asked Kimberly Plafke, the young-seeming executive chef who’s been working at Basil for a year, how the upheaval of the past year affected the restaurant. “Oh, it affected everything,” she says. “From the staff to the clientele to the cooking to the community’s views on us. But it was a blessing in disguise, really. We had seven to eight years of being revolutionary and then we got the kick in the butt we needed.”

“Are you still going to serve pizza?” I ask. In the past, owner Danny Branover told the New York Times that pizza was Basil’s main attraction, accounting for about $50,000 in monthly sales, and that he was suing rival restaurant Calabria for selling a dish that looked similar. What would Basil be without its pizza?

“We’ll still have pizza,” Plafke said. “We’re experimenting with lots of different kinds.”

The Jewish world can breathe a sigh of relief. The pizza I have is excellent, sprinkled with truffles, za’atar and a generous serving of cheese, lightly crisped at the edges — exactly the kind of pizza I imagine the Queen of England devouring on a cheat day.

So what’s Plafke’s dream for the future?

“The kosher community has lots of chains,” she says. “What it needs is a small, niche group of restaurants, mass producing while retaining quality.”

When you speak about Basil to employees (and employer), all roads seem to lead back to the subject of its reputation. “My non-religious relatives in South Florida knew about Basil,” Plafke tells me. “We’re giving the kosher community things it hasn’t seen before. I’m making a seafood charcuterie, but with two week aged tuna and seeped with sausages.”

“That’s an unusual flavor combination,” I say. I have to shout to be heard over the jazz. We both stand in front of the woodstone oven.

“I don’t like to think about how much that cost,” says Plafke. The oven is capable of burning both wood and gas, allowing a greater degree of temperature experimentation and culinary adventuring. Said oven is in an open kitchen, allowing diners to admire the artistry of the food being made without wondering why the service is taking so long.

“Do you think the price of the menu is alienating to your standard Jewish couple having a date night?” I ask. On Yelp, the menu is listed in the three dollar signs category, $$$, the second to most expensive category of restaurants on the site.

The chef gives the question some consideration. “If you want to have a date night on a budget, for under $100, you can,” she says. “If you want to go to town…”

“You also can,” I say.

“We’ve got a huge amount of regulars,” says Plafke. “You can get a ten dollar pizza anywhere. For a few extra dollars, you get a dining experience. Anyone who wants to have a good meal should come here. Of course we’re kosher and we’re catering to a kosher clientele but Crown Heights is evolving—”

“Some might say gentrifying,” I interrupt. I can’t imagine a restaurant like Basil succeeding here in the days before rich white people began migrating en masse to Brooklyn.

“Well, you see a lot of the same things happening in NYC,” she says vaguely. “I don’t know if this is different but we want everyone in the community who wants to have a good meal to feel welcome and enjoy.”

She brings me a hot toddy that tastes like afternoons spent playing in the snow as a kid. I savor it.

“We want other businesses to do well!” says an energetic Danny Branover, Basil owner. “We want everyone to make money! We’re trying to make kosher beautiful here. Aesthetics, quality, cleanliness. Some people think the stricter you are the more miserable you have to be. I don’t believe that.”

We’re sequestered in the corner of the restaurant and Branover is explaining to me his vision for Basil’s future.

“Food [served] as an experience, speaking to the global economy. We’re offering an eclectic kind of fare. We have a pasta with chipotle cream sauce. Multicultural food.”

Branover seems to be in a buoyant mood. I ask him about the lawsuit.

“People misinterpreted the lawsuit,” he says.

“Did they?” I say. “Do you mind if I record this?” He doesn’t mind. In the midst of this, he gets a call.

“No, we’re not really open, but we’d more than happy for you to join the party, it’s fine,” he says. “We’re closed for the public but if you really want to come…”

I wonder if this openness is Branover’s modus operandi.

“With Calabria, people misinterpreted the whole thing,” he announces. “They thought that I’m upset with somebody over the pizza shop. No, I’m more than happy to advance kosher businesses. The problem is we’re trying to send a message where we want to make Judaism beautiful. It so happens that the owners there are doing the total opposite. Their MO is leeching, you know, finding a successful restaurant and saying let me steal some of their business.”

“So it didn’t bother you commercially?”

“It didn’t bother me on the commercial side whatsoever. What bothered me is their approach….when you leech off someone else, that’s ugly Judaism. This wasn’t the first time they did it. Someone had to reprimand them. When somebody does something wrong, he should be notified, he should be slapped around a little bit, so he doesn’t do it to other people. We could withstand it. By me, it was more of an altruistic, ideological thing.”

“So this lawsuit was to teach them a lesson about ethics?”

“Strictly.”

“So there was no ego involved whatsoever? It was all business for you?”

“Exactly. And you know how many people came over to me that suffered? From some of the other places, they shake your hand for doing it because nobody else is doing it. People say, this is America. Yes, but do something revolutionary. Don’t be a leech.”

“But if Calabria started making canneloni with chipotle cream sauce, would you take him to beit din again?”

“No,” says Branover. “Because he learned his lesson. Do your thing, send a message across.”

“You think the message has been received?”

“I think so, because he keeps on calling me, saying are we friends? I say, listen, there’s a waiting list, you can be number 2,010.”

“You know I spoke with Clara, the old manager,” says Ami Nahari to me, the man who supplied the wines for the evening. “I saw that people flew in from Miami to be here. I said to Clara “what’s this about?” She said, “Its because the food doesn’t look kosher.”

Then Nahari beams at me and takes another sip of his fruity Californian Cabernet.

I privately wonder if this is the Jewish internalized shame about being too ethnic, too shtetl-Esque, too publicly Jewish. Can kosher food be universalized? Should it be?

But no matter! The eggplant carpaccio with crispy goat cheese is transcendent, salty and sweet in precisely the right amounts and spiced just so, like something I imagine Susan Sontag might’ve served in a literary salon.

Basil’s new signature dishes include branzini, baked, covered with yogurt, za’atar and sumac, light and flaky in texture but rich in flavor, like Shabbat dinner in a bite. There’s a schwarma with fish substituted for meat, that the waiters trip over themselves trying to pronounce. It’s a bit dry, the fish not an adequate substitute for the smokiness of the schwarma meat. There’s a goat cheese and eggplant cigar that reminds me of the years I lived in Tel Aviv. The goat cheese brulee is cooked to perfection, placed gracefully on the center of a bright bed of red cabbage, arugula and dates.

Five years from now, Basil will likely still be around to feed the Jewish community and the foodies of the world. The food is great, even if the intercommunity politics haven’t been.

Shira Feder is a writer for the Forward. You can follow her at @Xira_Feder

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO