His Cross To Bear

Image by Courtesy of the Barnett Newman Foundation

Image by Courtesy of the Barnett Newman Foundation

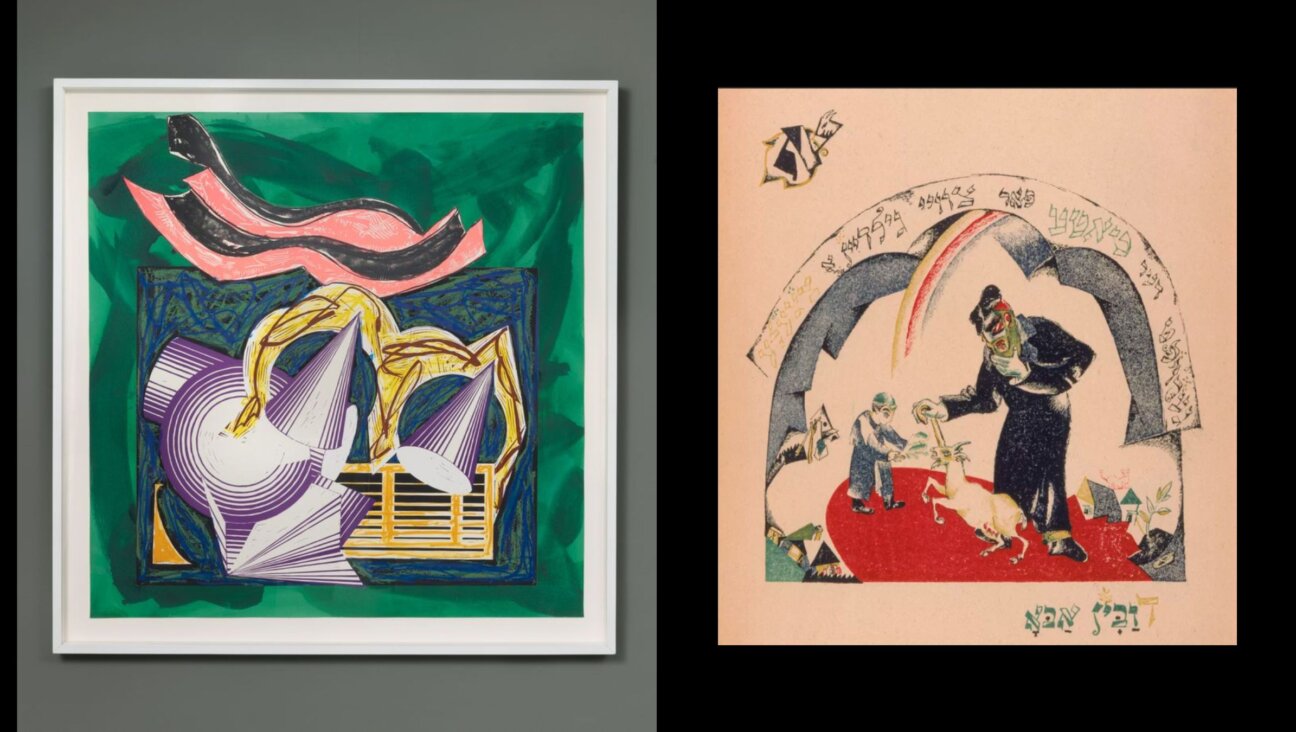

It’s tempting to read literal crucifixion imagery into Barnett Newman’s 14-canvas series, “The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani.” The portrait-oriented, black-and-white paintings and their bold stripes initially appear to be fully vertical in their thrusts, like crosses without horizontal shafts. But upon closer inspection, the vertical stripes, or “zips,” as Newman called them, which he created with the help of masking tape, bleed color from side to side, as a cross would if it were vibrating like a plucked guitar string. Each stripe, in a sense, consists of multiple miniature crosses, and subtle stains throughout the paintings could stand in as blood, sweat or tears.

Newman, who died July 4, 1970, insisted that his works didn’t literally represent the narrative of Jesus’ path to his crucifixion from the garden of Gethsemane. Instead, as Newman stated in a 1966 interview with poet and art critic Frank O’Hara on New York’s Channel 13, the series’s crucifixion imagery responds to the broader meaning of the cry that Jesus uttered on the cross: “Why have you forsaken me?”

The interview plays in a loop in the smaller room of the Tower Gallery of the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C., alongside the main gallery, where the series, which Newman created between 1958 and 1966, is on view through February 2013. The title of Newman’s series derives from the Aramaic for Jesus’ cry, although the phrase is sometimes rendered, perhaps more correctly, “Lama Shibaktani,” rather than “Lema Sabachthani.”

Despite — or perhaps because of — the direct New Testament reference in the title of the series, historians and critics have also noted Holocaust references in Newman’s work. “Other Jewish modern artists (like Chagall) dealt with New Testament themes,” wrote Harry Cooper, curator and head of modern and contemporary art at the National Gallery, in an email to the Forward. “In addition, there was a certain post-Holocaust tendency among Jewish thinkers to take the sufferings of Christ as a symbol of Jewish persecution.”

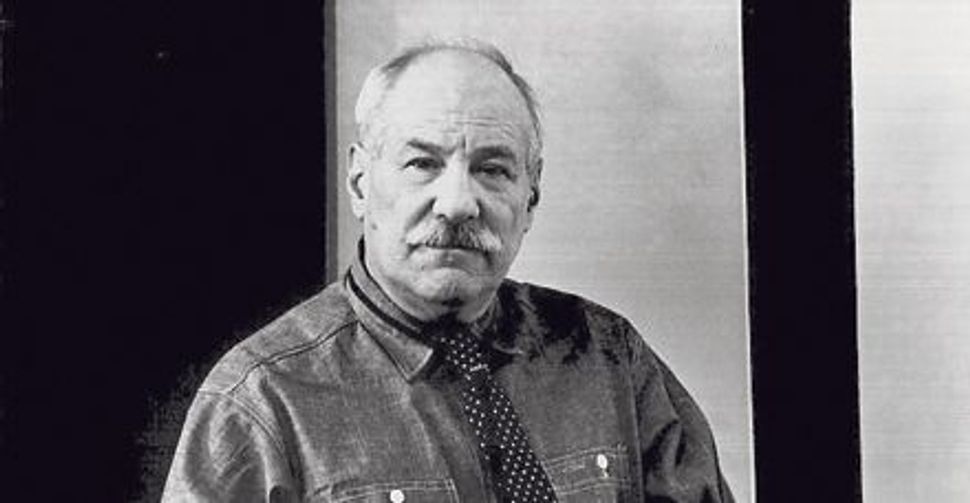

Newman was born in 1905 to a Zionist family of Polish immigrants on Manhattan’s Lower East side. In his 2006 book, “American Artists, Jewish Images” (Syracuse University Press), Matthew Baigell, a professor emeritus of art history at Rutgers University, writes that Newman was trained in Hebrew as a child and that he went to synagogue each year as an adult to recite Kaddish for his parents.

“Newman was not very observant, but he read the Old Testament (as well as the New) and was interested in Jewish mysticism. Many of the titles of his paintings reflect these interests,” Cooper wrote. Adam, Eve, Abraham, Uriel and Jericho are among the figures and places referenced in Newman’s titles. The Hebrew term makom, meaning “place” and also one of God’s names — referencing, in the abstract, God’s transcendence over particular places and His “occupation” of all spaces — was particularly important to Newman, Cooper added, noting, “He hoped such a place would be created between his art and the viewer.”

Is it surprising that a Jewish artist like Newman would address Jewish subjects through reference to the Crucifixion? In his 2007 book, “Abstraction and the Holocaust,” Mark Godfrey, a curator at the Tate Modern, in London, argues that Newman chose to title his series with a Christological reference rather than a reference to an Old Testament figure like Adam or Abraham, to “associate the paintings with… the intensity of the Passion,” as well as to make use of “an established metaphor that had been used to address the suffering of Jews and other groups under Nazism for almost 30 years.”

Artists who have used the Crucifixion as a symbol of Jewish suffering include, most notably, Marc Chagall, whose “White Crucifixion” (1938), at the Art Institute of Chicago, shows Jesus dressed in only a tallit loincloth. He is nailed to an enormous cross adorned by a Hebrew and Aramaic inscription that identifies him as the king of the Jews. The crucifixion is flanked by such Jewish symbols as a burning Torah scroll, a flying rabbi and a figure that arguably represents the Wandering Jew.

Other artists who have used New Testament imagery for Jewish purposes include Samuel Bak and Emanuel Levy, both of whose works were part of the exhibit “Cross Purposes: Shock and Contemplation in Images of the Crucifixion” two years ago at Ben Uri Gallery: The London Jewish Museum of Art. Levy’s 1942 “Crucifixion,” which was part of the Ben Uri show, pays homage to Chagall by dressing the crucified Jesus in a prayer shawl and phylacteries, although Levy’s titulus above the cross reads “Jude” in blood red.

Uncrossed: Newman?s straight lines seem to vibrate like plucked strings. Image by Barnett Newman, ?First Station,? 1958. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art

Some critics dispute the significance of Judaism, and especially of Kabbalah, in Newman’s work. Godfrey quotes Newman’s widow, Annalee Newman, who wrote in American Art in 1995, “The only connection that exists between Barnett Newman and the Kabbalah… is that Newman used kabbalistic language for the titles of several of his works. He did so, I am certain, because the language was poetic and fanciful.”

While Godfrey argues that Newman’s Jewishness — at least as a painter — could be overstated, he is convinced that one can say, at the very least, that Newman chose to present himself as an artist “who was interested in Jewish religious and literary traditions,” and also “as an amateur scholar, comfortable enough with religious literature to be able to use it and to defend his use if necessary.” The key for Newman, Godfrey concludes, was control over the meaning of his artistic project: “‘Yes’ to Jewish intellectual-artist-architect; ‘yes’ to scholar; ‘no’ to maker of ‘Jewish art.’”

But it’s also important to ask how deeply one can question Newman’s decision to mine Christian subjects. As my friend Tom Barron, a painter in Brookline, Mass., reminded me, Christian themes have long been a part of the canon, and it would be surprising for a Jewish artist not to draw on them.

Newman “did a good job with his taking a common, by his time clichéd subject and redoing it in abstract terms,” Barron said. “A Jew like Newman, removed from and unmoved by traditional Christian iconography, could see this eternal theme with fresh, ‘inner’ eyes.”

Perhaps by being removed from and unmoved by the cross, Newman was able to capture its symbolism even more poignantly.

Menachem Wecker blogs on faith and art for the Houston Chronicle at blog.chron.com/iconia. Follow him on Twitter @mwecker

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30