Can a new ritual shift our relationship to the Holocaust?

Hitkansut ritual 2019 Courtesy of Shalom Hartman/Youtube

How will we remember the Holocaust when all the survivors are gone?

This question has driven Jewish educators and historians as survivors have aged. Many educators treat it as a crisis; without testimony from those who actually experienced the atrocities, they will become easier to forget and deny. Holocaust denial is on the rise. There’s a push to record testimony and to create museum exhibits that display the horror, to ensure that even without living testimonies, there is proof of the atrocities.

Michal Govrin, an Israeli author, poet and theater director, is less worried about Holocaust denial than with how we remember the Shoah, and the frequent focus on violence and victimhood, which she sees as dehumanizing and disempowering. “Denial was there during the Shoah itself. It was exercised by the Nazis themselves,” she said.

Michal Govrin Courtesy of Michal Govrin

Focusing on why we remember the Holocaust instead of simply proving its existence, Govrin has come up with a new ritual to commemorate Yom HaShoah, called Hitkansut — “gathering” in Hebrew. With it, she wants to ask a more meta question: not just how to remember the Shoah, but what it means to remember.

I observed a training for the Hitkansut ritual run by Shalom Hartman’s North America division and led by Govrin and Rani Jaeger, who heads Hartman’s new Department of Ritual. The ritual has been run in Israel in recent years, and now the text has been translated.

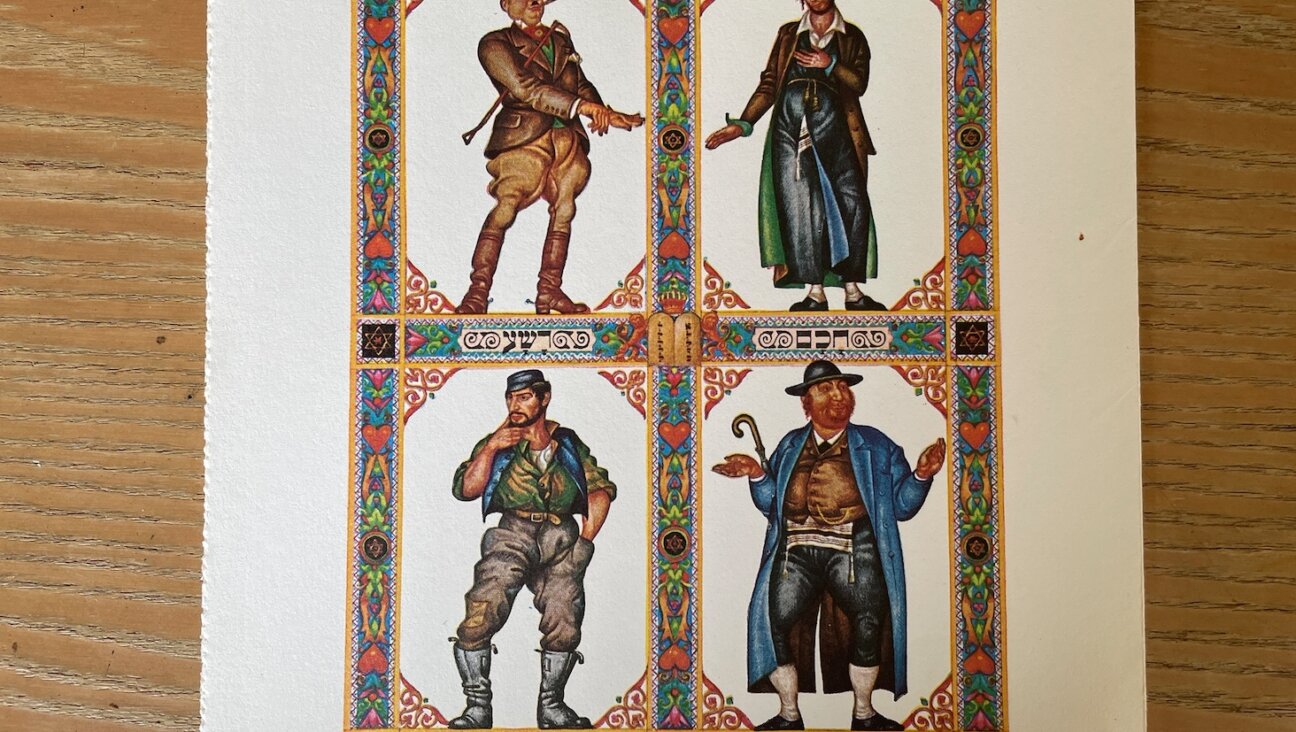

Govrin and Jaeger led the training group through the haggadah developed for the Hitkansut, which featured snippets of diaries, letters and poems from a diverse group of survivors, interspersed with liturgy written specifically for the ritual. I expected a serious, mournful ceremony, but there was music and poetry as well. Some excerpts of survivor testimony spoke about violence and anger, but others shared jokes told at concentration camps or told tales of celebrations in the ghettos. Participants were also asked to share their own history and memories.

The resulting experience moves from mourning to healing. The Hitkansut team has stressed that they want to move away from the victimhood often emphasized in Holocaust memorials, and instead emphasize individuality and community. They hope participants will feel empowered to work for change instead of despondent and overwhelmed.

I was curious why Govrin turned to ritual instead of the more familiar educational and historical tactics. While the Hitkansut haggadah does have bits of history and testimony, there are also modern poems and even a song by Leonard Cohen. The testimony is not the focus; it is interchangeable, and the haggadah is designed to be personalized to use the pieces of history, poetry or art that speak to the individual participants — including their own family stories. Instead, liturgy takes center stage, and they are actually partnering Haggadot.com to make the Hitkansut haggadah available with only the liturgy to encourage customization.

The Hitkansut ritual is the result of three and a half years of research, led by Govrin, working with writers and artists, museum curators and historians, as well as psychoanalysts and brain specialists.

“The same thing came both from the historians and from the brain researchers and psychoanalysts,” Govrin said. “Memory is not history. For history, we look to the past. For memory, we shape the present.”

That question of how to shape the present became the mission for Govrin’s team, and guided their turn to ritual. Ritual is enacted and done in the present, making it experiential; the rhythm of the liturgy is meant to engage the body in a prayer-like state that helps to involve people emotionally. This, hopefully, results in forming a different relationship to the Shoah, one that is present and relevant.

“History is about information, it’s about knowledge. Memory is a personal thing that a person experiences as a living experience,” Govrin explained. “So how to create memory is a different question than how to transmit history, and I think that we confuse the two terms when we talk about the Holocaust.”

This is not to say that the Hitkansut ritual will replace historical studies or education about the Shoah. But the hope is that ritual’s power might shift the way we relate to this event, helping it feel present and relevant even after survivors have passed away. And, hopefully, it will shift the story of trauma into one of strength.

“The individual and the community in the circle of memory go through a transformation that actually changes the legacy of the Shoah,” Govrin said. “Connecting to the human, to that extraordinary struggle to stay with dignity, even in the depths of the horror — that’s really the legacy of the Shoah.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30