Paul Auster, who wrote himself into his bestselling work, dies at 77

Known as a chronicler of Brooklyn, Auster was born in Newark

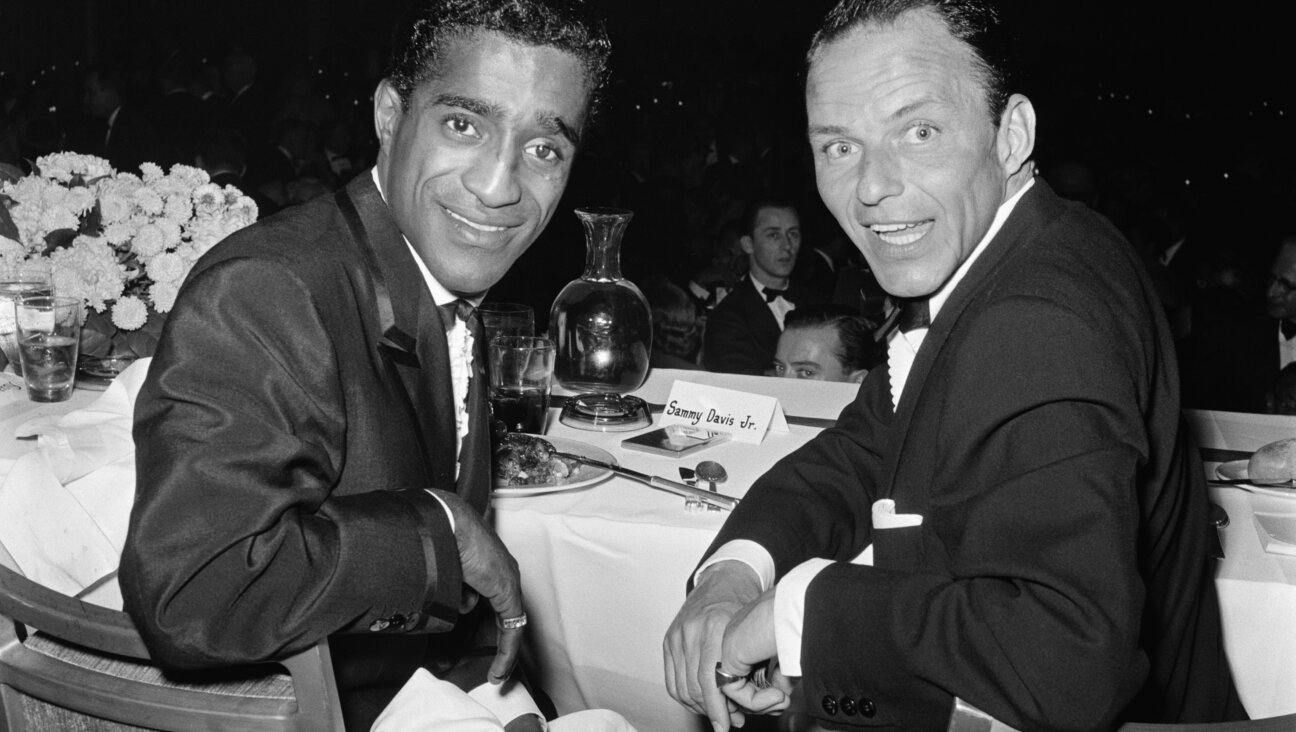

Paul Auster in 2018 Photo by JEFF PACHOUD/AFP via Getty Images

Writer Paul Auster, whose experiments with form, genre and autofiction gained him international acclaim, has died. He was 77. The cause of death was complications from lung cancer.

Best-known for his New York Trilogy, Auster was born in Newark, New Jersey, on Feb. 3, 1947, to Jewish parents Samuel and Queenie Auster. Samuel was a landlord with properties in Jersey City.

Auster’s relationship with his parents formed the basis for some of his work, with his father’s death prompting his career-launching 1982 memoir The Invention of Solitude and fraught father-son dynamics figuring into many of his novels.

Auster says he became a writer by always carrying a pencil, a practice he adopted after, when meeting his idol Willie Mays as a child, no one had a writing implement for an autograph.

Auster first moved to New York to attend Columbia University, where he pursued his bachelor’s and master’s degrees and met his first wife, the author Lydia Davis. Auster began his writing life as a poet while writing thousands of pages of “aborted novels.” He found his audience with works that resembled a grittier, Brooklyn-based Jorge Luis Borges.

1985’s The City of Glass is a piece of pulp detective fiction that refracts Auster’s own identity as writer and character in a game of literary telephone that jousts with Don Quixote. The marvel of the book, and the two subsequent ones that would make up The New York Trilogy, is that they became bestsellers despite puzzling layers of metafiction.

Into the 1980s and ’90s, Auster was prolific, writing the dynastic novel Moon Palace and the absurdist Mr. Vertigo (featuring a character named “Master Yehudi,” literally “Master Jew”). In 1992 he went biblical — or Hobbesian — naming a novel Leviathan.

Auster’s Jewishness wasn’t, as in the case of a certain other famous Newarkite-turned-New Yorker, always the main concern of his oeuvre, though it certainly was present, anticipating the work of his friend Jonathan Lethem, who would, in his own New York noir, Motherless Brooklyn, name a character Lionel Essrog. Many of Auster’s protagonists had Jewish names and were coded as, if not explicitly, Jews.

In an interview with Tablet, Auster explained that, when he wrote poetry, he “became interested in Jewish history and Jewish question,” influenced by Paul Celan, Edmond Jabès and Charles Reznikoff (Reznikoff’s last name is borrowed for an immigrant character in Auster’s novel 4 3 2 1.)

Jabès in particular taught Auster that “You could be a completely secular Jew and remain attached to history and even the philosophical groundwork of this faith.”

There was perhaps a discomfort with the actual shul-going part. In 2012, Auster appeared in conversation with Don DeLillo at Park Slope’s Beth Elohim. After some technical difficulties, he jibed “it’s not Broadway,” and, in a possible reference to his upbringing and the venue, “I knew I came to the wrong place when I was a kid.”

Jason Diamond, who reported on the event for Politico, recalled on X that “Auster really seemed to hate being in a synagogue.”

As Auster grew into an elder statesman of literary Brooklyn, his work became more eclectic. He dabbled in alternate universes, experiments in second person and wrote and directed films like the cigar-based ensemble flick Smoke (1995) and the jazz-inflected romance Lulu on the Bridge (1998).

Auster also continued to write nonfiction, publishing a 738-page biography of Stephen Crane in 2021, which, he told Irene Katz Connelly, was all written on a manual typewriter. (Despite a vast bibliography, Auster said he never was a fast writer — a good day’s work was one typed page.)

Auster was writing up to the end, publishing the novel Baumgartner — about a recent widower and professor — and Bloodbath Nation, a rumination on gun violence in America, last year. Baumgartner, Auster believed, might well be his last book and was certainly a confrontation with mortality. Both continued a career of grappling with major issues.

“The essence of being an artist is to confront the thing you’re trying to do,” Auster said in a 2017 interview. “If in wrestling with these things you manage to make something good, well, it will have its own beauty.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO