Neither Ashkenazi Nor Sephardi, Italian Jews Are A Mystery

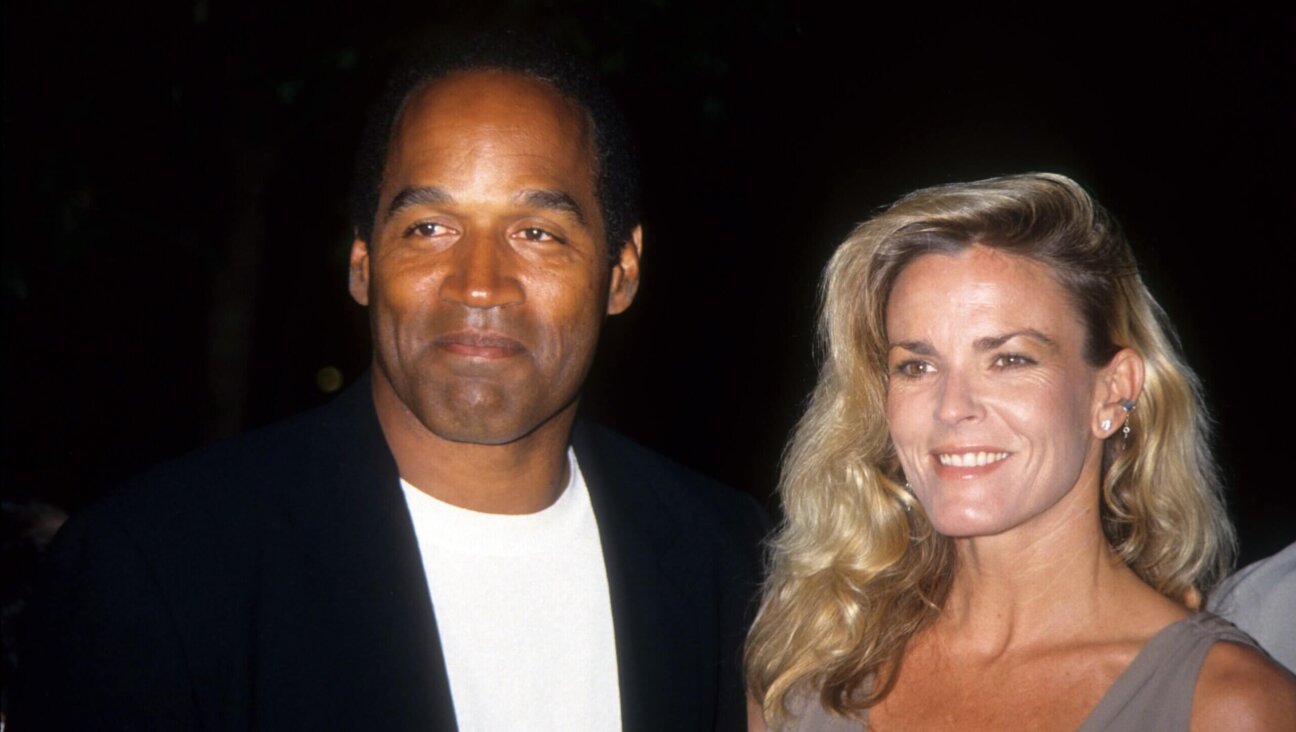

“The Feast of the Rejoicing of the Law at the Synagogue in Leghorn, Italy,” a work by Jewish British painter Solomon Alexander Hart (1850). (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons) Image by Wikimedia Commons

One often hears about two main cultural groups of Jews: Ashkenazim and Sephardim. Some also speak of a third group, Mizrahim, for the Jews who lived in modern Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Iran, Georgia and Uzbekistan.

But these groupings can be more complicated than they at first seem. There are three main ways of approaching the classification of Jews.

A first approach relies on geography. This approach applies the label “Ashkenazi” to Jews whose ancestors lived in the territory that in medieval rabbinical literature was called “Ashkenaz.” Ashkenaz corresponds to regions where the Christian majority spoke German dialects. Meanwhile “Sephardic” Jews are those whose ancestors lived in medieval Sepharad: Spain or, more generally, the Iberian Peninsula.

A second approach relies on language rather than place. According to this approach, modern Ashkenazim descend from Yiddish-speaking Jews. The ancestors of Sephardic Jews, on the other hand, spoke Spanish or Judeo-Spanish.

If following this linguistic approach we use “Mizrahi” to refer to the Jews who during the first half of the 20th century spoke (Judeo-)Arabic, then Jews from North Africa, regardless of their ancestry, would be counted among the Mizrahim.

A third approach classifies Jews based on the religious rites used in their respective congregations. This approach results in a much bigger class of Sephardic Jews than the first two, since at the beginning of the 20th century, numerous Jewish communities in the world whose members had no Spanish Jewish ancestors were following Jewish ritual in the Sephardic tradition.

These various approaches raise a question: Which category do Italian Jews belong to?

What About Italian Jews?

The most common point of view links Italian Jews to Sephardim. Implicitly, such an approach uses the last of the above three definitions. Indeed, during the last few centuries, the Sephardic rite was used in the territories, belonging to various states, that in the second half of the 19th century unified to form Italy.

However, according to the linguistic criterion, Italian Jewry should be viewed as a cultural group separate from all other Jews, since during the last few centuries, Jews living in various parts of Italy spoke Italian.

In this article, I will apply the first approach to classifying Jews to reveal the geographic roots of various strata of Italian Jewry, using surnames of Italian Jewish families to provide a good illustration.

This approach will reveal that the nucleus of Italian Jewry is related neither to Sephardim nor to Ashkenazim but a separate group entirely.

*

The ancestors of Italian Jews lived on the Apennine Peninsula for many centuries, where at least some of them have lived since Roman times.

In Jewish literature, there is no generally accepted term to designate these “indigenous” Jews, and they are often simply called Italiani, the Italian word for “Italians.” For many centuries, Rome, whose Jewish population was already large in antiquity, was home to the most populous Italiani communities.

Legend has it that the ancestors of four Jewish families in Rome were brought by the Roman Emperor Titus as Jewish prisoners after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 C.E. In Hebrew sources, these families appear as: min ha-tappuḥim (of the apples), min ha-adumim (of the red[-haired]), min ha-anawim (of the humble) and min ha-ne‘arim (of the youths).

The earliest known written mention of this legend is relatively recent. It appears in a book published at the end of the 16th century by a member of the first family, Rabbi David de Pomis (of apples, in Latin) of Venice. In the same century, we also find the earliest reference to the second family in a Christian document which makes reference to the family’s Italian name, de Rossi (of red[-haired]). The members of the third family appear in Italian documents as early as the 17th century under the singular Hebrew form anaw (Anau).

In Hebrew sources, the earliest references to these families correspond to the following centuries: 11th for Anau, 13th for both de Rossi and de Pomis, and 14th for the name meaning “of the youths.” But the bulk of Italiani Jews received hereditary surnames only during the 16th century.

The largest category of surnames is based on the names of places — usually the names of towns in the vicinity of Rome from which these families came to the capital city of the Papal States. Among them are Di Segni, Piperno, Pontecorvo, Rieti and Tivoli. When, in 1571, a census of the Jewish population of Rome took place, 278 families were listed as Italiani (indigenous) and 110 as Tramontani (foreign).

Jewish Migrations

Jewish migrants also came to Italy from the territories of modern France. They came in two primary, independent waves.

The first wave came with the expulsion of the Jews from France in 1394. Many of the expelled Jews settled in Piedmont, the region in northwestern Italy neighboring France. From the Middle Ages, Piedmont was part of the County of Savoy, a state that also covered territories that today belong to France. The Foa, Segre and Treves families came during this migration, and played important roles in the cultural life of Italian Jewry during the following centuries.

The second large group of Jewish migrants to Italy came from Marseille and other towns of Provence, a region annexed by the Kingdom of France at the end of the 15th century. The general expulsion of Jews from Provence occurred in 1501. The surname Provenzale (“one from Provence” in Italian) comes from these events, as are Passapaire and Sestieri.

Ashkenazi Jews represent the third major source of Italian Jewry. They came during the 13th-17th centuries from German-speaking provinces (mainly the southern territories that today correspond to Bavaria and Austria) as they escaped pogroms and anti-Jewish legislation. Ashkenazi migrants were particularly common in the northeastern and northern parts of the Apennine Peninsula: the Republic of Venice (especially in the cities of Venice, Padova and Verona), the Duchies of Milan and Mantua (today both in Lombardy) and the area of Trieste. They also settled in Piedmont, as well as central and even southern Italy.

For example, sources from Rome written from 1536-1554 mention a separate Ashkenazi congregation with its own synagogue called Scola Tedesca (German synagogue). Some of these migrants had surnames already, like Rappa from Nuremberg (later, this name gave rise to the Rappaport family, famous in Eastern Europe, with the second part, Port, coming from the town of Porto in northern Italy), Heilpron (in Italy, the most common spelling became Alpron) and Mintz (Italian Minci).

Yet, during this period, surnames were exceptional among Ashkenazi Jews. For this reason, many families acquired their hereditary names once in Italy. Katzenellenbogen is based on the name of the German town from which the founder of this rabbinical dynasty came to Padova. Numerous Ashkenazi families came to be called after the names of Italian towns where they lived. Among the examples are Bassano, Colorno, Conegliano, Pescarolo and Soncino. Gradually, the surname Tedesco (meaning “German,” with such variants as Tedeschi and Todesco) became one of the most common Italian Jewish surnames. Other famous Italian Jewish families of Ashkenazi origin include Luzzatto and Morpurgo.

Sephardic Jews appeared in Italy at different periods. Individual persons and families were already coming during the 13th-15th centuries.

After the general expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492, many Spanish Jews settled in Rome. Among them were bearers of such surnames as Almosnino, Corcos, Gategno and Sarfati. A smaller group (including the Abarbanels) settled in Naples and its region and lived there until the expulsion in 1541 of all Jews from the Kingdom of Naples.

During the 16th century, certain Spanish Jews who settled in the Ottoman Empire after the Spanish expulsion moved to important Italian seaports on the Adriatic Sea, including Venice and Ancona, where they founded the so-called “Levantine” Jewish communities.

The Arrival of “Portuguese” Jews

Beginning with the mid-16th century, a new group of migrants started to settle in the territory of modern Italy: the so-called “Portuguese” Jews. They were coming not only from Portugal, but also from Spain and territories ruled by the Kingdom of Spain, including the city of Antwerp, now in Belgium. All of these people were nominal Catholics: any profession of Judaism was prohibited and persecuted in their places of origin, and their attachment to Judaism was a secret.

In scholarly literature, these people, whose ancestors were mainly Jews converted to Christianity during the 1490s, are usually called “Marranos.” Upon their migration to countries where Judaism was tolerated, many families in question started to profess their Jewish religion openly.

Initially, their influx was concentrated in Ferrara and Ancona. At the end of the 16th century, however, Venice and Livorno became their main destinations. Large groups of “Portuguese” (ex-Marrano) Jews also settled in Genoa and Piedmont during the 16th-17th centuries.

All of these migrants founded large communities that followed the Sephardic rites. Some families restored the surnames of their Jewish ancestors who had lived in medieval Spain: Aboab, Attias, Mazaod and Namias. Others took surnames indicating to which one of the three Jewish castes their ancestors belonged: Cohen, Levi and Israel. Yet, the majority retained the surnames they used as nominal Catholics, including Fonseca, Lopes, Mendes, Pinto and Rodrigues.

Gradually, Livorno — the only city in the territory of modern Italy with a large Jewish community in which no ghetto has ever been established — became the main Jewish Italian center, attracting numerous Jews of various origins from other parts of Italy. The gradual propagation of the Sephardic rite in Italy was primarily due to the influence of “Portuguese” Jews.

During the 17th-20th centuries, numerous Jews from North Africa settled in Italy (mainly in Livorno), bringing there such surnames as Busnach, Elhaik, Racah and Sasportas.

All of this shows the degree to which the history of the Jewish communities in any given geographic area can be complex. In such situations — which are common in Jewish history — one can easily be misled by oversimplified opinions or assertions that use ambiguous terms.

Alexander Beider is a linguist and the author of reference books about Jewish names and the history of Yiddish. He lives in Paris.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!